When Hope Outpaces Calculation, Mechanisms of Collective Perceptual Error in a Moment of Protest

On 8–9 January 2026, nationwide protests in Iran culminated in one of the deadliest crackdowns in recent history. This essay explores how symbolic power, media framing, and distorted risk perception shaped a collective perceptual error.

By Elham Hoominfar

Friday, 20 February 2026

Abstract

On 8–9 January 2026 (18–19 Dey 1404), large-scale public gatherings in hundreds of cities across Iran signaled a rare moment of social mobilization. Many participants came into the streets with their families, as if the long-awaited “moment of transformation” had finally arrived. It was a moment of collective hope. Yet this surge of protest culminated in one of the most violent crackdowns of recent years. The simultaneity of collective hope and sweeping repression raises a central question: how did a segment of protesters arrive at a relatively optimistic assessment of the balance of forces and the likelihood that the risk of repression would diminish?

This essay examines the mechanisms that shaped such an assessment. Drawing on conversations with participants in the protests and an analysis of the media and political context of the period, I argue that a constellation of symbolic, media-driven, and discursive factors, alongside deep structural crises, contributed to the formation of what may be called a collective perceptual error, in which the coercive capacity of the state was not accurately calculated.

Using sociological concepts such as symbolic power and hegemonic discourse, the article suggests that the production of political hope in authoritarian settings can function simultaneously as a force for mobilization and as a condition for misjudging risk perception. The aim here is not to render political judgment or assign legal responsibility, but to understand the social mechanisms that generate collective expectations in moments of crisis.

The Moment When Everything Seemed Possible

Although the protests began in the bazaar, they quickly spread across cities and rural towns throughout Iran, places where years of inefficiency and accumulated resentment toward the Islamic Republic had taken root. In those days, an encouraging public perception began to crystallize that a sufficiently large presence in the streets could tip the balance of forces and bring down a government widely seen as incapable and exhausted.

Part of that perception rested on reality. Many Iranians no longer wished to live under the weight of sustained authoritarianism, pervasive violence, and systemic mismanagement. The economic situation had become acute; roughly one in three Iranians was living below the poverty line, and for large segments of society, the burden had become intolerable. Within a matter of days, a tacit collective agreement had emerged that something decisive could be initiated together. It was as if people had been waiting for a spark to connect them, and that spark came, first with the strike of bazaar merchants. With mobilization in Abdanan, then in the major cities, and finally with the call issued by Reza Pahlavi, the exiled former Crown Prince of Iran, whose voice, amplified through media channels, assumed a hegemonic position within the protest landscape.

The Great Massacre of 8–9 January 2026 (18–19 Dey 1404)

In January 2026, one of the most harrowing crimes in modern Iranian history unfolded. The Islamic Republic, whose record includes the mass execution of thousands of political prisoners in the 1980s and episodes in which more than one hundred people were killed in a single day outside a mosque, once again deployed what many witnesses described as a machine of death. This time, it moved through alleyways, major thoroughfares, city centers, small towns, and villages alike. According to the number of victims whose identities have been verified to date, more than seven thousand people were killed over two days. Other estimates under review place the total death toll at more than thirty thousand.

Reports of assaults on hospitals and medical centers, of wounded protesters being shot at close range, of the arrest and killing of medical staff and physicians, have prompted the filing of a case against the Islamic Republic at the International Criminal Court in The Hague on charges of crimes against humanity. Taken together, these accounts point to violence on a staggering scale.

In the aftermath, Iranian society appeared stunned. The atmosphere was saturated with anger and hatred, but also with grief. As one witness in Tehran put it, “The volume of our mourning is beyond our capacity.”

Another witness, who had been present on a Tehran street with her teenage daughter, described a profound and lasting trauma. “This level of brutality against unarmed people is unbelievable,” she repeated. Weeks later, she still suffers from nightmares. During the day, the sound of several motorcyclists approaching is enough to make her body tremble and trigger panic. Fighting back tears, she said, “You do not know what kind of people, what young people were slaughtered. It was as if an order had suddenly been issued to shoot at any moving body.”

A different protester recalled that “many people wore multiple layers of clothing to protect themselves from pellet guns, but they attacked us with live ammunition.”

Another witness, his voice breaking repeatedly, said, “You cannot imagine what we saw. They did not even spare their own people. When they attacked, they even killed some of their own plainclothes forces. But more terrifying than that is having to live in this city beside these killers.”

Yet the structural crisis in Iran remains unresolved. The massacre has only deepened accumulated anger and resentment. The state continues to implement economic policies many view as predatory. Under such conditions, serious protests will likely re-emerge. If they do, strategies of street mobilization will require careful reassessment and reflection.

Why Did a Sense of Security Exist?

According to one witness, people came into the streets not only with their families, children, and elderly relatives, but even with their dogs. Did they not believe in the violence and ruthlessness of the Islamic Republic’s security forces? What had happened that led one woman in Tehran, who had gone out with her eighteen-year-old university student daughter, to say, “I felt safe. We went out on Thursday night, and we did not know that killings had already begun elsewhere. If I had known, I would not have taken my daughter. The next day we went out again with the family. Honestly, I thought there might even be people among us who were there to protect us.”

Another protester said, “I thought when they saw such a large crowd, people who had come with their families, maybe they would retreat, maybe the sheer size of the crowd would stop them, maybe next week we would all be celebrating.”

In some cases, what appears to have formed was a false sense of security. Even children and the elderly entered the streets with the belief that “if you go out, you are not alone and you will be supported,” that a protective force existed, or that the government feared international reaction and would not dare to kill its own citizens. These assumptions generated a dangerous illusion that the risk perception of repression had shifted downward. Among some, there was also a tendency toward speculation about foreign intervention or even war, a horizon of hope shaped in part by media narratives.

Recent events seemed to reinforce such thinking. The killing of Ismail Haniyeh in the heart of Tehran, followed by what was described as a “twelve-day war,” during which the residences and workplaces of senior Revolutionary Guard commanders, nuclear scientists, and high-ranking security officials were reportedly destroyed through precise strikes by the Israeli military, contributed to the sense that the regime’s upper ranks were vulnerable. Perhaps, some reasoned, this time too the leadership would be targeted similarly, and the people in the streets would be able to carry through a major transformation.

The Imagined “Revolutionary Moment”

Another dimension of the story concerns the state’s coercive apparatus. In classical theories of revolution, a transformative moment emerges when rulers lose the capacity to repress, when the machinery of coercion weakens and fractures. Revolutions do not unfold simply because people gather in large numbers, but because the balance of forces shifts decisively.

A shared decision to take to the streets and a sense of solidarity are necessary for large-scale change, yet they are only one side of the equation. Beyond the brutality and violence of the Iranian state, there was also a strategic question that could not be ignored.

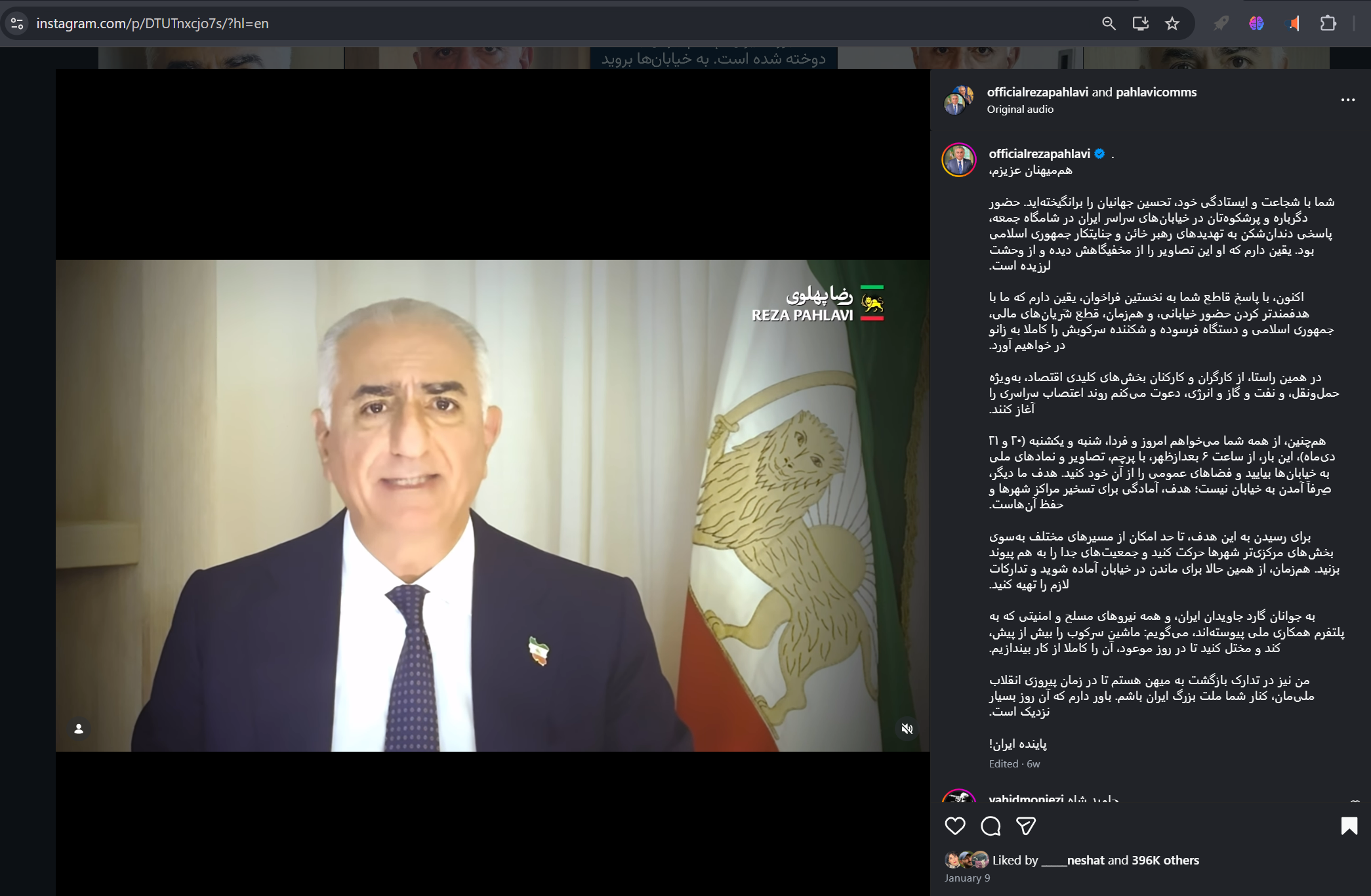

During those days, a particular perception gained traction, that the formation of a massive, million-strong crowd would overwhelm the regime’s security forces, that many would retreat, and some would even defect to the side of the protesters. “If we seize the streets, the regime will quickly lose both the capacity and the will to repress,” declared Reza Pahlavi in a public call on Friday, 1 January 2026 (12 Dey 1404).

One witness, who attended the demonstrations in an Iranian city with his wife and child, later said that he had been certain they would return to the streets the following week to celebrate victory, that the Islamic Republic would no longer exist. Such expectations illustrate how a horizon of hope can crystallize around what appears to be a revolutionary opening, even when the structural conditions of state power remain intact.

Narratives and the Construction of a Horizon of Hope

Field accounts from protesters suggest that media narratives can exert a powerful influence on both risk perception and political hope. Dominant narratives are rarely constructed overnight. They take shape over time, through repetition and reinforcement.

If we return to the so-called twelve-day war and trace the media discourse from its conclusion to the days preceding the January protests, a pattern emerges. Persian-language media outlets based outside Iran, with large domestic audiences reached first by satellite and later through the internet, repeatedly emphasized that the war had not truly ended, that only its first phase had passed. Through talk shows, debates, news segments, and social media amplification on platforms such as YouTube and Instagram, diaspora media cultivated the idea that the Islamic Republic was on the verge of collapse, living out its final days. According to this framing, only one final act by the people, combined with military assistance from Israel and the United States, assistance portrayed as imminent and almost inevitable, would bring about the regime’s dissolution.

At a moment of severe economic crisis and widespread political exhaustion, these outlets depicted the horizon of hope as drawing ever closer. It is precisely here that one may critically examine hopeful or media-driven discourses without confusing them with the primary agent of violence, the Islamic Republic itself. The issue is not to displace responsibility, but to understand how symbolic processes shape expectation.

Multiple factors converged to produce what may be described as a collective perceptual error. The timing of certain events is instructive.

On Sunday, 28 December 2025 (7 Dey 1404), nationwide protests began in response to economic collapse, the sharp devaluation of the rial, the national currency, and mounting public discontent. Demonstrations first took shape in Tehran and soon spread to other cities.

Between Tuesday, 30 December 2025 and Wednesday, 7 January 2026 (9–17 Dey 1404), protests continued across most provinces. Markets closed in several cities, and diverse social groups appeared in the streets.

On Thursday and Friday, 8–9 January 2026 (18–19 Dey 1404), the days that would become known as the Great Massacre, a public call by Reza Pahlavi mobilized a broad segment of the population. Some understood immediately what was unfolding; others would soon learn that one of the bloodiest episodes in contemporary Iranian history had taken place. Demonstrations expanded in many cities, including Tehran, Mashhad, and Rasht. At the same time, the government imposed a nationwide internet shutdown to restrict the flow of information. Satellite broadcasting from abroad, however, continued uninterrupted.

Parallel developments were amplified across media and social networks, shaping the dominant interpretive frame. On Friday, 2 January 2026 (12 Dey 1404), President Donald Trump wrote in an official post on the social platform Truth Social: “If Iran shoots peaceful protesters and kills them violently, the United States will act to save the people. We are locked and loaded and ready to act. Thank you for your attention. President Donald Trump.”

On Sunday, 4 January 2026 (14 Dey 1404), Trump told reporters that he was closely monitoring events in Iran and that if violence against protesters escalated, the United States could respond very forcefully. Speaking publicly aboard Air Force One that same day, he stated that the United States was “watching very closely” and that Iran would be “hit very hard” if its security forces attacked demonstrators.

On Thursday, 8 January 2026 (18 Dey 1404), in an interview with Fox News, Trump said, “People were killed. Some of them, the crowd was so large, they were trampled. It was terrible. The crowd was enormous. Their enthusiasm for overthrowing the regime is unbelievable. People were killed, but many were trampled as people ran. We will see what happens.”

In the days following the outbreak of protests, he repeated several times that help was on the way.

After the large-scale massacre, in a public speech addressed to Iranian protesters, Trump declared: “To all Iranian patriots, continue the protests, take control of your institutions if possible, and remember the names of the killers and abusers who harm you. Remember their names, because they will pay a very heavy price.”

Taken together, these statements, amplified through satellite television and social media, contributed to a political atmosphere in which external intervention appeared not only conceivable but imminent. Within that symbolic environment, the perceived balance of forces shifted in the imagination before it shifted in reality.

Ignoring a Variable, The Repressive Machine

A closer look at the sequence of events suggests that a fundamental variable was underestimated: the existence of a heavily armed repressive apparatus. According to one witness in Isfahan, a group of protesters seized the local broadcasting center, as similar government offices had reportedly been taken over in other cities. But the crucial question remains: What was the plan afterward? As this witness recounts, security forces soon arrived and opened fire on the crowd. Similar scenes unfolded elsewhere.

This raises a difficult question. Why did encouraging media outlets and diaspora leaders not adequately anticipate the possibility of a lethal response from the regime’s coercive machine? Or, if they did, why did they appear to assign it insufficient weight and fail to offer practical guidance for confronting such an escalation?

For example, in his public call of 2 January 2026 (12 Dey 1404), six days before the Great Massacre, Reza Pahlavi had declared that “seizing the streets of Tehran and other major cities would significantly accelerate the regime’s fall.” He urged people to overcome fear by creating roadblocks along key arteries and major highways. Through such actions, he argued, “the regime will quickly lose both the capacity and the will to repress.”

In these appeals, the probability of violent repression appeared diminished. Pahlavi expressed firm confidence that “with the formation of a massive, million-strong tide of people, the regime’s repressive forces will not be able to withstand it. Many will retreat, and some will join the people.” Within this narrative, the anticipated weakening of the coercive apparatus became part of the horizon of hope (افق سیاسی), even as the structural power of the security state remained intact.

When Calculation Goes Wrong, A False Sense of Security

In his call for the demonstrations of 8–9 January 2026 (18–19 Dey 1404), Reza Pahlavi suggested that recent gatherings had already demonstrated a pattern: “Over the past few days, I have followed your demonstrations and marches closely… Despite the repression of the authoritarian regime, you have been admirable, and you have certainly noticed that crowd density forces security forces to retreat and increases the likelihood of defections. Therefore, it is important to preserve this concentration and scale.”

Months earlier, on 23 July 2025 (2 Mordad 1404), he had announced that “at least 50,000 members of the Islamic Republic’s governmental and military forces have joined the National Cooperation Campaign to help bring about the regime’s overthrow.” This claim was repeatedly amplified and highlighted by Iran International, Manoto TV, and numerous monarchist Twitter and Instagram accounts. Public documentation of the financial structures of these two satellite networks remains limited, and detailed transparency into their funding mechanisms is unavailable. In media and political circles, speculation has circulated that they may be influenced by regional investors, including those from Saudi Arabia or Israel, and some critics have described them as politically aligned with right-wing currents. Whatever the accuracy of such claims, their reach inside Iran is undeniable.

In addition, a tweet by Mike Pompeo, former U.S. Secretary of State during Donald Trump’s first administration, asserted that Mossad forces were present alongside the people in Iran’s streets. Mossad is Israel’s elite foreign intelligence agency. This message was reinforced by a Persian-language Twitter account affiliated with Mossad that repeatedly referred to such a presence. The financial publication Barron’s reported that the official Persian-language Mossad account on X had posted messages including, “Go to the streets. The time has come. We are with you,” adding that “not only from afar and verbally, but we are also with you in the field.”

These statements and claims circulated widely on social media and were broadcast repeatedly on Iran International and Manoto. After 8 January 2026 (18 Dey 1404), when internet and telephone services were shut down across Iran, satellite transmission allowed Iran International to remain accessible to viewers inside the country. Yet based on available evidence, during those two days, the scale of the massacre was not fully disclosed on air. In other words, the immediate danger unfolding in the streets was not clearly conveyed. At the same time, several activists attacked Vahid Online, an independent source who was publishing videos of killings as they were received, accusing him of attempting to frighten people and discourage them from entering the streets.

Placed side by side, these elements help explain why one street protester told me bluntly, “We were set up.” In the atmosphere that had taken shape, a false sense of security emerged, in which symbolic power and mediated expectations reshaped risk perception before events on the ground could correct them.

Political Hope and the Risk of Collective Disillusionment

Mass mobilization is indispensable for any transformative political moment. Yet hope that exceeds the actual distribution of power can impose high costs, culminating in deep disillusionment, diminished future participation, and a pervasive erosion of trust.

Diaspora media outlets, with tens of millions of satellite viewers and extensive Twitter and Instagram networks, constructed interpretive frames aligned with their own political orientations. Whether intentionally or not, they appear to have removed the regime’s coercive apparatus from the logical equation. From a sociological perspective, it is here that a large-scale collective perceptual error took shape.

My conversations with eyewitnesses, along with evidence circulating within Iran, suggest that Persian-language outlets based abroad, particularly Iran International and Manoto, played a significant role in shaping the mindset of some protesters. Among many slogans, such as “Long live the Shah” or “This is the final battle, Pahlavi will return,” circulated with the implicit belief that rallying around a single figure could generate cohesion and increase the movement’s chances of success.

What was striking, however, was that only hours after the Great Massacre, on Saturday, 9 January 2026 (20 Dey 1404), Reza Pahlavi issued a new call that appeared either unaware of or silent about the events of the previous forty-eight hours. In that message, he spoke of preparing to return to the homeland and urged people to take to the streets on Saturday and Sunday to seize the central districts of major cities, while he himself was preparing for his return.

At the same time, these same media outlets cultivated a fantasy of war, selling the prospect of foreign intervention to segments of Iranian society. This dynamic must be understood alongside the widespread frustration that followed years of gradual reform efforts by Iranian civil society, efforts that were repeatedly met with repression and bloodshed. In such an environment, external rescue narratives could find receptive ground.

From a sociological standpoint, such media and the leadership narratives they promote are not necessarily direct causes of violence. Yet media framing, the production of political expectations, and the consolidation of discursive hegemony can shape risk perception, recalibrate levels of hope, and influence the trajectory of collective action. A sociological critique of outlets such as Iran International and Manoto, and of the political discourse associated with Reza Pahlavi, is therefore less a matter of legal accusation than of examining how meaning is constructed, how collective expectations are formed, and how psychological and political consequences unfold from such constructions.

Political media are not merely conveyors of reality; they are producers of meaning and collective affect. Within this framework, hero-making, the amplification of hopes disproportionate to the actual balance of forces, and the transformation of politics into spectacle may ultimately weaken collective agency and complicate the formation of a viable alternative for Iranian society.

What Should Be Learned for the Future?

Let me emphasize once more that the principal agents of the Great Massacre of January 2026 (Dey 1404) were the rulers, commanders, and executors of the Islamic Republic. This fact must not be marginalized in any analysis.

At the same time, the role of political actors, dominant discourses, and the organizational networks surrounding them deserves careful evaluation. Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran’s former monarch, has at various times sought to align himself with protest waves within the country and to turn them into political opportunities. In previous episodes, however, these efforts often failed to generate sustained or large-scale mobilization. During the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement, he similarly sought to secure a place within the protest landscape and, at times, presented himself as its leader. Yet, according to some observers, a tension existed between his political framework and the egalitarian and progressive discourse that animated that movement.

The forward-looking, equality-oriented ethos of “Women, Life, Freedom” sat uneasily with the idea of leadership by a male figure from a former royal dynasty. At one point, he removed the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom” from his Twitter page after having displayed it. Reports also circulated suggesting that some of his supporters responded to the movement’s demands and values with dismissive or hostile rhetoric, contributing to gendered verbal confrontations and, in some cases, physical tensions among protesters.

The depth of economic crisis and public dissatisfaction during the recent protests was such that almost any well-known political figure, had they been sufficiently visible, might have been able to mobilize segments of society through a public call. The society appeared to be waiting for a signal to converge. From this perspective, the level of response to certain calls for mobilization can be understood in structural terms, as a product of broader social conditions rather than solely the personal attributes of a single actor.

Nevertheless, Pahlavi’s political orientation and the networks surrounding him influenced the representation and direction of certain mobilizations, guiding them in ways that did not necessarily align with sober assessments of social change. It is equally arguable that if other political figures, including those with different backgrounds within Iran’s political structure, had played a more active role at that moment, patterns of mobilization and trajectories of change might have unfolded differently.

A form of temporary and hegemonic leadership appeared to crystallize around Pahlavi, reinforced largely through repeated media representation. Reports indicate that some protest videos circulated from inside Iran were overlaid with audio supporting him. At the same time, it is undeniable that on 8–9 January 2026 (18–19 Dey 1404) and in the days surrounding it, slogans endorsing him were heard at certain gatherings. Part of this support rested on the belief that he could play a transitional leadership role and guide Iran toward democracy. Yet the transitional framework he has proposed emphasizes centralized authority and remains distant from established democratic models.

Moreover, Pahlavi has not presented a detailed and structured plan for political transition or institutional transformation. His statements about returning to Iran have largely remained symbolic. His strategy appears less grounded in organizing domestic constituencies and more reliant on the prospect of external pressure or support, in other words, scenarios involving foreign intervention or war.

In the absence of an organized and independent alternative, the journalistic field can reproduce narratives that are implicitly one-sided. The media field is not merely a channel for transmitting information; it is a field of forces and struggles in which actors seek to redefine power relations and secure their positions, as Pierre Bourdieu argues in On Television (1998, p. 40). Within such a field, the logic of speed and simplification, particularly dominant in visual media, can flatten social complexity and highlight particular horizons of expectation (Bourdieu 1998, p. 29). Moreover, when media become the principal mechanism through which public reality is defined, what is made visible is tacitly stabilized as what exists (Bourdieu 1998, p. 19).

This process can be understood through the concept of symbolic power. Language and discourse do not simply reflect reality; they can constitute it, inducing people to see and believe in a particular version of the social world (Bourdieu 1991, p. 170). Under such conditions, media representations may contribute to a form of misrecognition regarding the actual balance of forces, especially when structural assessments of possibility give way to immediate horizons of hope.

In matters of political representation, a group acquires social existence through the delegation of authority to a spokesperson. The representative does not merely mirror the group but symbolically constitutes it (Bourdieu 1991, p. 204). The effectiveness of political speech thus derives less from its content alone than from the institutional position of the speaker (Bourdieu 1991, p. 111). Media-driven leader construction can therefore be understood as part of the production of symbolic authority, a process that may channel collective expectations toward horizons not fully aligned with the real distribution of power.

My aim here has not been to anatomize a massacre, but to examine how a protesting population, one that correctly sensed a historic opening, nonetheless experienced a collective perceptual error regarding the “revolutionary moment.” Confronted with one of the most entrenched and violent repressive states in the region, segments of society appear to have misjudged the durability and capacity of the coercive apparatus.

Given the current climate of restriction and crisis in Iran, comprehensive and precise information about the events of January 2026 remains incomplete. Yet even partial analysis may help illuminate the mechanisms that shaped collective expectation. Such understanding is essential if future mobilizations are to avoid being propelled once again toward catastrophe.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Logic of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990. Originally published 1980.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Translated by Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Bourdieu, Pierre. On Television. Translated by Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson. New York: The New Press, 1998. Originally published 1996.

© IranDraft

More by Elham Hoominfar

Structural Crisis and the Expectation of Revolution

Nationalism, War, and Affection for One’s Homeland

We are dedicated to looking beyond headlines.

We bring the full story and context to you when it comes to news from Iran.