After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness for the Lurs?

The history of the Lurs is scarred by catastrophes under the Pahlavi regime. The puzzle is how that same regime, or its admirers, reshaped memory so that mass killings are minimized and the butchers of Lorestan are not only forgotten, but forgiven.

By Forough Asadpour

January 7, 2026

Introduction

The spark for the latest round of protests was struck in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, where small shopkeepers, far from affluent, joined the unrest. Almost immediately, cities in Lorestan and other regions with significant Lur populations poured into the streets. In parts of Tehran and northern Iran, the sound of protest could also be heard. Some analysts have rightly focused on economic conditions, poverty and corruption, the soaring dollar, rising taxes on small and mid-sized merchants, and the steady decline in bazaar incomes. In smaller cities and among non-bazaar social groups, the central issues remain livelihood insecurity, economic devastation, and systemic corruption within the state.

Persian-language media outlets abroad, meanwhile, amplified monarchist slogans with remarkable enthusiasm, promoting the return of the Pahlavi dynasty as a plausible and attainable alternative. This intervention has, in fact, weakened the protest movement and hindered its expansion. Available evidence suggests that a majority of those killed in this latest wave of protests have come from Lur communities.

I have become deeply interested in and sensitive to the social history of Lur-inhabited regions. I admit that until recently I knew almost nothing about Lur history, their traditional modes of production, or the forms of life that shaped Lur societies before and after the rise of the Pahlavi state. This ignorance is itself a product of what passes as “Iranian” historiography.

Nationalist historians typically begin with the Achaemenids and Sassanids, proceed through hostility toward Arab and Turkic invaders, a hostility that translates domestically into Turkophobia and Arabophobia and externally into regional antagonism, and conclude with the salvation of the Persian language and Shi‘ism as a form of “protective dissimulation” for preserving Iran and Persian culture. In this narrative, Reza Shah Pahlavi is celebrated as the heroic founder of the modern nation-state.

The Left, for its part, has often written history through the lens of the growth of the working class and capitalism, and the eradication of “feudalism” and “backward, reactionary tribal relations.” In this way, it has entered into an unspoken, negative alliance with nationalist historiography, portraying the entire pre-Pahlavi era as a period of ignorance and stagnation, as if the emergence of a centralized state and “modern productive relations” automatically ushered in widespread progress for the majority of the population. There are, of course, notable and growing exceptions to this trend, among them the invaluable work of Ervand Abrahamian.

Writing “history from below,” that is, narrating the lives of “peoples without history,” to use Marx’s and especially Engels’s term for stateless nations in Europe, discussed in the Ukrainian Marxist Roman Rosdolsky’s work, translated to Persian by Mohammad Ebadi-Far and myself, has held little appeal for intellectual forces oriented toward class war, the seizure of political power, and the establishment of socialism. Many intellectuals from these so-called “non-historical peoples” were themselves absorbed into elite frameworks, whether left or right, preoccupied with an abstract notion of “Iran,” and largely neglected their own societies and the task of writing their histories.

This neglect is compounded by a broader reality: political and intellectual forces in Iran, shaped by a teleological historical outlook and hostility toward anything they believed to be temporary or destined to vanish, treated with indifference whatever seemed incapable of resisting “capitalism, modernity, the nation-state, and modern civilization.” Ways of life deemed backward or reactionary were dismissed outright, excluded from serious analysis or consideration.

As a result, regional social structures, diverse modes of production, and varied forms of collective life, with all their virtues and flaws, were seen as theoretical and practical obstacles to achieving the supreme goal, whatever that goal happened to be. Intellectual forces, whether labeled left or right, were not necessarily pleased by the destruction of everything that failed to serve this higher aim, but they were certainly not troubled by it.

As foreign scholars have noted, among them Lambton, cited in John Foran’s work, the destruction of millions of nomads, including the massacre of the Lurs, took place with the silent consent of Iran’s urban population and settled communities, as well as its intellectual elites. Similarly, when the Democratic Party government in Azerbaijan granted official status to the Turkish language, newspapers and intellectual circles in the center portrayed this as a source of division and anxiety. They advised the party’s leaders that, for the sake of national unity and the resumption of a nationwide struggle, the issue of linguistic recognition should be abandoned. All Iranians, they insisted, belonged to a single race and bloodline, and the Turkish language should not cast a shadow over the struggle of a unified nation, as argued in The Past Is the Guiding Light of the Future (گذشته چراغ راه آینده است).

Differences themselves, racial, linguistic, national, cultural, or economic, came to be framed as a symbol of division and hostility toward “Iran,” “the Iranian nation,” or “the working class.” This logic persists today. The result has been political intolerance and an aggressive, exclusionary mindset among centralists and Pan-Iranists, a disposition whose consequences are now fully visible.

I have an intellectually serious friend. Some time ago, we were talking about the situation of the Lurs. He spoke of the massacre carried out against them by the first Pahlavi ruler, the same Reza Shah whose name is today being shouted, out of desperation, by some Lur protesters, and by others as well. Whatever limited knowledge I now have of the Lur question, and whatever sensitivity I have developed toward this ethnic people, or nation, and their suffering, I owe largely to those conversations and to the reading that followed.

It remains deeply regrettable that the history of the Lurs and their fate has been presented in scattered, selective, and fragmented ways across various books, with no coherent historical-anthropological synthesis. To my knowledge, no work, or body of work, exists that undertakes a systematic and sustained study of the Lurs as a subject in their own right, or at least none that I have encountered.

If Azerbaijan, Ahvaz, Kurdistan, and Baluchistan remain, for now, in a state of watchful waiting and have not fully joined this round of protests, one can at least partly attribute this to their dissatisfaction with the political staging by Persian-language media outside Iran. These outlets have sought to impose a deeply unpopular leadership figure on nations whose strong historical memory resists accepting him as a potential restorer of a monarchy that was a declared enemy of non-Persian peoples.

These societies do not wish to become part of a nationwide movement that still lacks any meaningful recognition of national plurality, linguistic diversity, or political solutions such as federalism or regional autonomy. Not only are such solutions absent, but even discussing them remains intolerable to the dominant discourse. The mere invocation of the name of a notorious dictator who set out to annihilate all non-Persian peoples provokes anger and fear among these communities. For this reason, the ethnic, national, and regional dimensions of the current protests demand careful attention.

The question, then, is this: if Turks, Arabs, Turkmen, Qashqai, and Kurds are, at least at this stage, standing at some distance from the ongoing protests, why are the Lurs so visibly active in the middle of the field, and why have they not reacted negatively to monarchist slogans?

I hope that the present text, prepared under pressure and in haste, can serve as a starting point for further discussion among Lur political activists and others.

[At the time of writing, I have just learned that, simultaneous with Reza Pahlavi’s call for coordinated slogans, Kurdish political parties have issued a call for a general strike in Kurdistan on Thursday, 1 January 2026. It remains to be seen whether, as in the previous round of protests when Abdullah Mohtadi participated in the Georgetown meeting and described Reza Pahlavi as possessing significant “social capital,” coordination between him and Kurdish parties will again take shape. Another notable aspect of the statement is the complete omission of any reference to Pahlavi or the monarchist alternative, a silence that the authors pass over entirely, and one that is hardly reassuring.

Equally striking is a passage in the statement declaring:

“The bloody suppression of protests in Kermashan, Ilam, Lorestan, and especially the crime committed in Malekshahi, is a continuation of the same naked policy of state violence to which the Islamic Republic of Iran has resorted in order to survive. Arrests, street repression, and the intimidation of protesters are not signs of power, but an open admission of fear and crisis within this regime.”

A few lines later, the statement adds: “We stand alongside the resilient people of Kurdistan.”

This is despite the fact that the Lurs have played a powerful role in this round of protests, yet no mention is made of these people, whether as a nation, an ethnic group, or a collective subject. Everything is once again recorded as “Kurdish,” and in the name of Kurdistan alone.]

What follows is a report that combines a summary of my conversations with my Lur friend and the results of my own recent reading, conducted over the past two or three days, with a focus on the Lurs, their tragic history, and the massacres inflicted upon them by Reza Shah Pahlavi. Knowledge of history, particularly of the recent past, is always useful.

My aim is to offer, within the limits of my ability, a brief examination of Lur modes of life and systems of production, and in this context to analyze the foundations of their repression and massacre at the hands of Reza Shah’s army. At the same time, I seek to shed light on the scale of the killings, deportations, and forced displacements, processes that amounted, in effect, to the destruction of a culture, a way of life, a mode of production, a history, and ultimately, a people.

This destruction extended not only to human communities but also to the natural environment, the geography, and the animals with which daily life was intimately and inseparably intertwined.

Finally, I will return to a question raised by my interlocutor: why has a refined collective political consciousness, inspired by earlier forms of identity, language, and ways of life, forms that were annihilated through unimaginable violence under Reza Shah, failed to crystallize among the Lurs as a significant intellectual foundation for debates about political authority and governance in Iran?

Three Modes of Life and Production in Iran

We owe a debt to John Foran for his efforts to challenge the one-dimensional approach of much of Iran’s center-oriented Left and the ahistorical political economy that has long dominated its analyses. By “center-oriented Left,” I mean a perspective that, for decades, treated the development of capitalism as a teleological, linear process, mechanically progressing through the familiar stages of primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, and socialism. Within this framework, capitalism was assumed to be not only inevitable but even, implicitly or explicitly, the dominant and progressive form of Iran’s socio-economic and political organization. In this view, Reza Shah’s centralized state, under the banner of Iranian nationalism, appeared as an unavoidable and, at times, even positive historical achievement.

Foran, by contrast, speaks explicitly and boldly of three distinct modes of life or systems of production in Iran, and supports this argument with official statistics and empirical evidence. He describes Iran’s socio-economic structure as a composite, intertwined, and tripartite formation. The first mode consisted of sedentary rural production, based on peasant and sharecropping labor, in which the direct producer received a portion of the final product. The second mode comprised tribal and nomadic communities, organized around pastoral nomadism and tent-dwelling, moving seasonally between winter and summer pastures with their herds, while often practicing agriculture on a seasonal basis alongside herding. The third mode involved urban production, including small-scale commodity production and the expansion of capitalist urban industries.

These modes of production were directly reflected in the composition of the population. Around 1900, corresponding to 1278–1279 in the Iranian calendar, Iran’s urban population stood at approximately 2.07 million people, or 20.9 percent of the total population. Tribal and nomadic groups numbered about 2.47 million, roughly 25.1 percent of the population, while the rural peasantry accounted for approximately 5.32 million people, or 54 percent of the total. Viewed through this lens, the relative sizes of the populations engaged in each mode of production offer insight into the balance of political power, the relationships among different forms of production, and the broader economic and, by extension, governmental structures of the country, a discussion that would require a separate and more extended analysis.

Four decades later, by 1940, or 1318 in the Iranian calendar, a strikingly different demographic picture emerges. Iran’s urban population had grown to 3.2 million, accounting for 22 percent of the total population. The tribal and nomadic population had shrunk dramatically to about one million people, just 6.9 percent of the population. Meanwhile, the rural peasantry had expanded to approximately 10.3 million people, representing 71.1 percent of the country’s inhabitants.

What stands out most clearly in these figures is the rapid and severe decline of the tribal and nomadic population over the course of these forty years. This decline naturally extended to their livestock as well, setting off a chain reaction that affected the country’s overall food supply and the policies adopted by the central state. One concrete outcome was a sharp increase in food imports, a point documented in The Past Is the Guiding Light of the Future.

What unfolded during this forty-year period was nothing less than a full-scale war against a specific mode of production and against the regional communities whose lives were organized around it. This war involved the seizure of land and the stripping of collective ownership, the killing and elimination of community leaders, the dispersal of regional collectivities across other parts of the country, and, more broadly, the destruction of more than half of the nomadic population through gradual attrition and, at times, outright massacre, carried out through centralized and ruthless repression.

Barrie, cited in February, notes that of the 2.47 million pastoral nomads recorded in 1900, only about one million remained by 1932, or 1311 in the Iranian calendar. The rest had either died or been forcibly settled. What a remarkable “achievement” for Iranian civilization, for Reza Shah Pahlavi, and for the modernists and pamphleteers who continue to celebrate him.

As a result of the suppression of this way of life and this system of production, the lands of many tribal and nomadic leaders were transferred directly to Reza Shah. In addition to his already vast holdings, he redistributed portions of these confiscated lands to senior army officers, high-ranking state officials, merchants, and contractors. Foran writes that Reza Shah became notorious for land-grabbing. Nearly all the lands of Mazandaran, his native region, and large swaths of Gilan and Gorgan, major rice-producing areas, were converted into his private property. His estates eventually encompassed some six million acres. He also held shares in numerous factories, companies, and domestic monopolies. When he left the country, his deposits at the National Bank had risen from one million rials in 1930 to seven million pounds sterling.

To transform the army into the cornerstone of his power, Reza Shah imposed enormous financial burdens on the poor and on the country’s economy as a whole. It is estimated that the military consumed around 40 percent of the national budget, while its size expanded from roughly 10,000 to 40,000 troops. Yet when Reza Shah was forced to leave Iran in September 1941, this costly army was incapable of mounting even minimal resistance against the Allied forces occupying the country. Its principal “success” lay not in defending Iran, but in suppressing tribes and nomads, peasants and workers, political and economic opponents of the Shah and his regime, and the dissident elites who challenged his authority.

Among the settled agricultural population, the balance of political power also shifted in Reza Shah’s favor. The political influence of large landowners declined relative to that of the monarch, yet the relations of production between landlords and peasants remained unchanged, despite being a central political demand of the Constitutional Revolution. Thus, while landlords lost political leverage vis-à-vis the Shah, their wealth and economic power remained intact. The lower classes derived no material benefit from these political transformations.

Foran offers a harrowing account of the conditions faced by Iran’s 3.5 million peasants and their families. Life for peasants had never been good, but toward the end of Reza Shah’s reign, it deteriorated further. The typical peasant family’s diet consisted of bread and tea for breakfast, bread and yogurt for lunch, and bread, yogurt, and tea for dinner. In the 1950s, or the 1330s in the Iranian calendar, the United Nations estimated that the average Iranian adult consumed fewer than 1,800 calories per day, a level lower than that found in all other impoverished regions of the Middle East. Public health conditions were equally dire. Infant mortality rates reached 50 percent, life expectancy in rural areas stood at just 27 years, disease was widespread, and most villages lacked even basic sanitary facilities.

As noted earlier, tribal populations were particularly devastated by Reza Shah’s policies of martial rule and the systematic eradication of tribal and nomadic societies. Foran writes that Reza Shah’s experience suppressing tribal unrest after 1921 led him to conclude that “tribespeople” were unruly, aberrant, rebellious, and illiterate savages, left to languish in a primitive natural state. Ann Lambton adds that such views and policies enjoyed the support of the country’s non-tribal population.

Within this intellectual and political climate, the state mobilized its full force against the tribes. It first sought to subjugate them to the authority of the central government, a process that took the form of prolonged, continuous, and relentless warfare. It then resolved to “civilize” them, pursuing this goal through forced settlement programs and the compulsory sedentarization of tribal and nomadic communities.

The Lurs: Dispossession, Massacre, Forced Relocation, the Killing of Leaders, and the Price of Roads and Railways

With that framework in view, we can move closer to the question of the Lurs. Reza Shah’s army, after killing leaders and members of Lur tribal communities, proceeded to disarm them. That was not the end of it. Their seasonal migration routes were blocked, forcing them to remain in a single location, to farm, and to abandon pastoral herding. Yet the lands allotted to them were often agriculturally worthless.

Hossein Makki, in the sixth volume of his Twenty-Year History of Iran, writes that, from the outset of Reza Shah’s reign, the consolidation of power required the compulsory sedentarization of tribes and the elimination of their major leaders. Tribal communities were then relocated to other parts of the country. Makki notes, for example, that some Lurs from the cold regions of Lorestan were transferred to Varamin, even though Varamin’s conditions did not correspond to the seasonal ecology of Lorestan for pastoral households. In Varamin, these Lur communities could no longer sustain livestock raising; they became unemployed, fell into begging and misery, and ultimately perished.

William O. Douglas, in Strange Lands and Friendly People, addresses the situation of the Lurs in scattered but revealing passages. He recounts bitter testimonies, offered by survivors of once-organic Lur communities who now lived in an almost servile condition, shattered and dispersed by ruthless force. In one part of his journey, Douglas encounters members of the Sagvand tribe, still numbering around 40,000, ragged and impoverished, compelled to work as sharecroppers for landlords approved by the Shah, including a certain Poursartip. These tenants, Douglas reports, were perpetually in debt to their landlords, unable to escape the cycle of obligation and hardship.

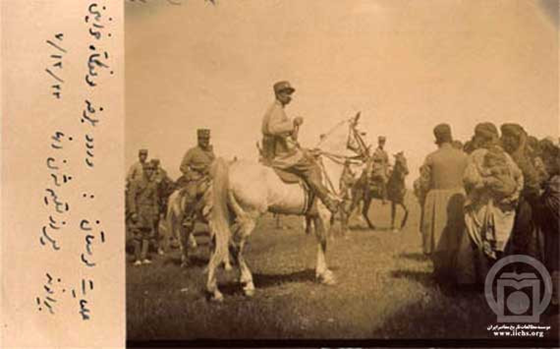

Douglas adds that the extreme poverty of the Lurs was also the product of plunder by the Iranian army. The tragedy, he writes, was bound up with Reza Shah’s policy of bringing the tribes to heel, a program that did not solve a single problem for the pastoral communities it targeted, but intensified deprivation and exclusion, culminating in massacre and looting. Douglas describes one of the most disgraceful chapters of Reza Shah’s reign, written by one of the Shah’s officers, remembered among Iranians, or more precisely among the Lurs, as the “Butcher of Lorestan,” a reference to Ahmad Mir-Ahmadi.

The story, as Douglas relays it, begins in 1936, when the Iranian government decided to build a motor road in Lorestan. The Lurs opposed the plan, clashes erupted between the army and Lur tribes, and the situation escalated after the Lurs killed one of the Shah’s officers and seized Falak-ol-Aflak Castle in Khorramabad. The Shah replaced the dead officer with another high-ranking commander, dispatching him with reinforcements and military equipment. When government forces retook the fortress, they immediately hanged eighty Lur leaders. One officer who had participated in the killings told Douglas, “We left the bodies hanging on the gallows for three days, so it would be a good lesson for the remaining Lurs.”

Foran, too, notes that Reza Shah dispatched military governors to Lur areas to conscript soldiers, and when communities resisted, both ordinary people and their leaders were imprisoned, physically punished, or sent before firing squads. The “uniform dress” law, introduced in 1928, offered state agents a ready pretext for repression in Lorestan. Foran also describes how road-building and railway construction increased the state’s ability to monitor and punish the Lurs. In the state’s view, forced settlement made taxation easier, and restricting population mobility simplified control, yet the combined social, economic, cultural, and psychological impact on Lur communities was devastating. Population numbers fell sharply, as did the volume of pastoral production.

Comparable patterns can be found in the history of Indigenous resistance in North America, the societies now often referred to as First Nations. Suspicious of state control and of the true intentions of state agents, many Indigenous communities rejected “progress” and resisted, sometimes through armed conflict, efforts to build roads and railways across their lands.

This scale of human loss in Iran was accompanied by losses in livestock production nationwide. Meat, leather, hides, and dairy products all declined. Pack animals used for transport became scarcer. The poor lands assigned to displaced communities, combined with the withdrawal of financial support, made the transition from one form of rural production to another punishingly difficult, pushing newly “sedentarized” tribal people to the furthest margins of society.

The pastoral nomadic mode of production was anchored by two primary social strata, tribal leaders and ordinary members, both of which were severely weakened by forced settlement and the broader assault on tribal life. Qashqai, Bakhtiari, Boyer-Ahmadi, and Mamasani leaders also paid a heavy price for their resistance to Reza Shah. They were exiled, placed under surveillance in Tehran, had their property confiscated, were imprisoned, and in some cases were ultimately killed. Others chose accommodation and collaboration.

For ordinary tribal people, living conditions deteriorated sharply under Reza Shah, bringing severe impoverishment across multiple dimensions. The reach of Pahlavi state agents, forced disarmament, military raids on settlement sites, compulsory conscription, and other coercive measures produced predictable outcomes, declining livelihoods, social degradation, and collective ruin. Foran argues that the hardships of forced settlement inevitably shaped tribal consciousness and contributed to political mobilization. Rather than generating legitimacy, the Pahlavi regime grounded its authority in threats, weapons, and force, and, within these politicized societies, ethnic minorities emerged who resisted Persianization. Some Lurs became industrial workers in the oil sector, as with the Bakhtiari employed in oil fields, and experienced a different form of politicization.

Foran’s account, however, risks making the story too neat. The hypothesis he proposes does not apply uniformly to all these people. The Lurs, for reasons to be discussed later, did not reach the same level of national or political consciousness. Moreover, Turks and other non-Persian peoples have never accepted the category of “national minority” for themselves. They have maintained, instead, that Iran is, and remains, a multi-national country, and that the former mamalek-e mahrouseh, the protected domains, cannot be reduced to a single nation and a single language. Nor does one kind of politicization necessarily exclude another. Class-based political consciousness need not be severed from, or opposed to, national and regional consciousness, a dynamic observable, for instance, among workers in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Why politicized class consciousness need not be in rupture with national-regional consciousness is a separate discussion, for which Rosdolsky’s work, in the translation by the author of this essay and Mohammad Ebadi-Far, is recommended.

For discussion of the forced sedentarization of the Lurs, one should also turn to Operations in Lorestan (The Siege of Khorramabad and the Tarhan Operation), edited by Kaveh Bayat. Bayat’s introduction offers a partial but illuminating account of the catastrophic conditions imposed on the Lurs.

The central government’s effort to restore authority in tribal regions, Bayat writes, took more than a decade, much of it consumed by military confrontation. In both of the incidents he examines, responsibility for the uprisings, he argues, lies more with army commanders than with any inherent “criminality” or “malice” of the tribes. Amir-Lashkar Amir-Ahmadi, through actions such as arresting and executing Lur leaders who had accepted government guarantees, and through the killing and capture of large numbers from the Birunvand tribe in the winter of 1923–24, created the conditions for a widespread uprising the following spring, again met with the arrest and execution of leaders who had accepted assurances.

In 1925, oppression and harsh treatment by disarmament and revenue agents, combined with the maneuvering of Reza Shah’s representative, Brigadier Shah-Bakhti, who exploited local rivalries, produced the Tarhan uprising and the subsequent military operation. It was not some inevitable “tribal temperament” that made war unavoidable. These events, like many others during Reza Shah’s era, emerged from grievances that might not have turned violent or wasted the country’s human resources had there been any legal mechanism for articulation and redress. In tribal regions, the unchecked power of military authorities narrowed the space so severely that little remained besides revolt and the violent expression of discontent. Even when a partial form of judicial review became possible, as during Shah-Bakhti’s governorship in 1925–26 and the Tarhan operation, it occurred only after the rebellion expanded and the army proved unable to suppress it, leaving officials no choice but to remove the “culprit” and respond to the complainants’ demands.

Bayat also writes of a “Pahlavi innovation” in methods of repression. During the Khorramabad operation, Lur communities witnessed mass killings of Birunvand women, men, and children, alongside the arrest of several leaders, including Sheikh Ali Khan Birunvand and Mehr Ali Khan Hasanvand. On the night of January 5, 1924, state forces attacked without warning from multiple directions, killing several hundred people living between Tang-e Zahedshir and Tang-e Rabat, and taking roughly the same number captive. Soon after, the detained leaders, along with Hossein Khan Sardar Ashraf and other Lur chiefs, were executed. These actions had a profoundly destructive impact on the Lurs, not least because the violence was carried out under the banner of “settlement,” and accompanied by humiliating practices, including presenting many captured men, women, and children as tenant laborers for local landowners.

That same year, in early March, Amir-Ahmadi declared in a commission meeting that members of the tribe were ready to become tenants, and that any landowner needing tenants could request that individuals from the tribe be sent to him. This directly echoes Douglas’s account of the Sagvand, a tribe of roughly forty thousand, effectively handed over, even sold, as tenant labor to landlords favored by Reza Shah.

Reza Khan praised Amir-Ahmadi for the “cleansing of Lorestan,” the discipline and suppression of Birunvand leaders, and the crushing of “bandits.” Yet only a short time after this commendation, the Lurs rose again, leading to the siege of Khorramabad. Amir-Ahmadi was recalled to Tehran, replaced by Brigadier Shah-Bakhti, tasked with suppressing “bandits and rioters.” After a period, Amir-Ahmadi returned to Lorestan, with the aim, as it was put, of “erasing the name of the Lur from the page of Lorestan.”

In another book on Reza Shah’s Iran, by Iraj Rudgar-Giya, we read that suppressing Lur uprisings was among Reza Shah’s highest priorities in the pursuit of centralized power and the crushing of tribal society, especially the “brave Lurs of Lorestan,” because the strategic north-south Trans-Iranian Railway and the military road from Khorramabad to Khorramshahr had to pass through their territory. The plan met resistance from allied Lur tribes, who fought superior military forces with far more rudimentary weapons. Rudgar-Giya also recounts the case of a fourteen-year-old Lur boy, Yadollah Khan Ghazanfari, brother of Ali Mohammad Khan Ghazanfari, who, despite surrendering under oaths sworn on the Qur’an by Reza Khan’s commanders, was hanged. He notes that on December 9, 1927, in the mountains near Chul Hol, the boy confronted government forces, fought until his last bullet, and was then killed.

Richard Tapper, in Reza Shah and the Creation of Modern Iran, writes that Reza Shah’s hostility toward Iran’s tribal communities is well known, and most scholars agree that he broke the backbone of the tribal system in Iran. Pursuing a program of national unity and the creation of a new, independent, secular, Persian-speaking country, Reza Shah viewed nomadic tribes as embodiments of what he sought to eliminate, foreign cultures and languages, loyalty to hereditary tribal chiefs rather than to the homeland, an “primitive” way of life, and geographic mobility, which made law enforcement and control difficult. He also feared the extent to which tribes had been used, in the past and present, as instruments of foreign powers.

One might note the irony. This fear of foreign manipulation comes from a ruler who came to power through an illegal coup supported by foreign forces, who fled the country under their threatening pressure and the inaction of the expensive army he had built for internal repression. His son, Mohammad Reza, returned through the same foreign will, orchestrated a coup against Mossadegh, and ultimately fled as well, leaving behind the costly military apparatus that had been built, above all, to police the domestic population.

The Absence of a Politicized National-Regional Identity Among the Lurs

In the course of my conversations with my friend, he spoke at length about the geography of Lorestan and the wider mountainous zones where Lurs have historically formed a majority. The region is sharply rugged and difficult to traverse. Arable land is scarce, redirecting water to fields is hard, rain-fed agriculture predominates, and even the towns that exist in Lur-inhabited areas, Borujerd among them, sit at the margins of these societies rather than at their center. In earlier times, tribal bazaars had a kind of seasonal vitality, expanding and contracting with the rhythms of migration.

To explain what has preoccupied my interlocutor, the apparent absence of a strong regional or national identity among the Lurs, he points to a difference he considers decisive, one that distinguishes the Lurs from other peoples of Iran. This difference is the lack of a contiguous co-ethnic population, or a national kin group, across Iran’s borders. Unlike Kurds, Turks, Baluch, or Arabs, the Lurs had no neighboring co-ethnic community on the other side of a border that could serve as a cultural and political reference point.

Lur tribes did, of course, travel beyond the frontier at times, even approaching Baghdad, but their routes were not anchored in major political or intellectual centers. As a result, the seeds inside Lur tribal structures, the early nuclei from which new ideas might circulate, could not easily take shape. There was no sustained channel through which developments in the surrounding world could enter and be converted into institutions, associations, newspapers, or a fragile but formative middle stratum capable of absorbing new political languages.

There were exceptions, especially from the Qajar period onward, and more clearly in the second half of Naser al-Din Shah’s reign. Some sons of tribal leaders, and even some leaders themselves, traveled abroad. Sardar As‘ad, Ali-Qoli Khan, and, later, his sons, went to Europe and underwent significant intellectual transformations. Sardar As‘ad acquired broader horizons and developed liberal views. His son, Khan-Baba Khan As‘ad Bakhtiari, formed the Star of Bakhtiari Party on the eve of Reza Shah’s rise. He and his associates advanced reformist ideas and were influenced by left currents. They spoke, in principled terms, about ethnic and tribal questions, health care, education, and even gradual settlement.

All of this occurred before Reza Shah. Then, Reza Shah killed the local leadership. He eliminated figures such as Khan-Baba Khan, son of the second Sardar As‘ad, and Ja‘far-Qoli Khan Sardar As‘ad Bakhtiari, who died brutally in Qasr Prison. He left no one capable of organizing and leading their people. In this way, even early capacities, even the first embryonic forms of organized leadership, did not have the chance to grow. With no cross-border network of co-ethnic kin to compensate, no external corridor through which ideas and solidarities might circulate, the result was an intellectual vacuum, a void that prepared the ground for a form of mental, cultural, and political colonization in the aftermath of Reza Shah’s massacres.

The Mental and Cultural Colonization of the Lurs

The Lur educated strata, my friend argues, were formed under Reza Shah and out of the ashes of a scorched Lorestan, that is, after the region had been conquered by the army. Reza Shah, he says, established what were called “tribal schools,” and forced the sons of tribal khans into them. The resemblance to the methods of white settler colonialism toward Indigenous peoples is difficult to miss.

Lur elites were trained according to the state’s worldview, with a particularly strong pan-Iranist ideology. The general line of pan-Iranist politics was to place Kurds, framed as a branch of an “Aryan” people, against Turks, and then to set Lurs against Arabs, using them as instruments of repression. Reza Shah and his circle achieved limited success in some areas, but with the Lurs, they succeeded decisively. A manufactured middle class was produced, loyal to the state's pan-Iranist aims. In the 1940s, the first outcomes of these institutions became visible: Lur intellectuals and a rising middle-class elite emerged in public life as fiercely assimilated pan-Iranists, self-Persianizing, and deeply intolerant. A radically assimilated elite was produced.

Dr. Houshang Azami Lorestani, a well-known Lur dissident figure, was, at one point in his youth, a member, even an active member, of the Pan-Iranist Party. In this sense, the Lur middle class was formed from the beginning as something borrowed and assimilated. It did not arise organically from local histories, local cultural materials, or collective memory. The first and second generations of this middle stratum included figures who said, without embarrassment, that our fathers were savages. Reza Shah helped us, the Lurs, by forcing them to settle. Tragically, my friend insists, this attitude persists.

For these intellectuals and this middle-class elite, Lur tribal communities were “wild,” a source of disorder, and it was better that Reza Shah stripped them of everything and destroyed their world.

A “Trail of Tears” for Lorestan

That is one side of the story. The other is the army's movement across the Lur regions, memories that have not faded. My friend describes the army’s campaigns in terms that invite comparison with a holocaust, an annihilatory violence.

Most readers will recognize the American history known as the “Trail of Tears.” Between 1830 and 1850, the U.S. government forcibly expelled five major Indigenous nations from the southeastern United States: the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole. The forced relocation followed the Indian Removal Act, signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. People were compelled to march hundreds, perhaps thousands, of kilometers, facing cold, hunger, and disease, and large numbers died along the way. Survivors described the route as “the road where we cried.” The central motive was the seizure of fertile lands by white settlers, and anti-Indigenous racism played a decisive role.

My friend argues that something comparable happened to the Lurs. Not only were their leaders and khans eliminated, killed, and erased, but ordinary people died in large numbers along the routes of forced displacement. The sick and the elderly were left behind in the open. The destination was Khorasan. Lurs were marched on foot toward the northeast or distributed among villages along the way. Their fate became one of killing, massacre, exile, and dispersal.

Reza Shah achieved his goal. Forced settlement of “unruly” tribal communities, followed by their “civilizing,” produced results within two decades. Along with these people and others like them, a way of life and a culture rooted in proximity to nature were destroyed. Iran had once exported meat to neighboring countries. After the confiscation and destruction of livestock, Iran became a meat importer. This “Pahlavi development,” in this view, reflected no creative or productive strategy, only coercion and extraction.

Before Reza Shah, even within reformist tribal circles, gradual settlement had been discussed as a partial solution, as in the Star Party and among certain reform-minded khans, including Mohammad-Taqi Khan Chahar-Lang Bakhtiari. The proposed approach was slow, principled, and incremental. Reza Shah, by contrast, destroyed everything in Lorestan and in the Lur tribal regions. After Lorestan was turned into scorched earth, no meaningful industry arrived, no genuine urbanization followed with its necessary infrastructure, and nothing replaced what had been annihilated. Today, Lur regions remain among the most deprived areas of the country.

Continuities Under the Islamic Republic

The Islamic Republic, my friend contends, continued the same Reza Khan-style militarism. Military bases multiplied, under both the Pahlavis and the Islamic Republic. Military careers and teaching were presented as priority paths for Lurs. Lurs were taught to enter the army, to guard Iran’s borders, and culturally to become pan-Iranists and devoted readers and reciters of the Shahnameh. In this telling, Persians and others have not read the Shahnameh as intensively as the Lurs have.

The railway project linking the center to Khuzestan for oil and the destruction of Lur lands are another dimension of this tragedy. Livelihoods were ruined, land was confiscated, livestock was destroyed, and mass migration followed, comparable to what Turkic populations experienced at various times. In Tehran’s popular culture, Lurs became a symbol of stupidity and helplessness. Lur regions, rich in water and natural resources, were treated as extraction zones. Under the Islamic Republic, minerals are extracted, then shipped to factories built in Persian-majority regions. This system has persisted, with no meaningful force able to halt it.

The first generation of educated Lurs, produced under conditions of deep assimilation, became, in many cases, instruments of repression against their own society, a pattern also seen among Turks.

The Left in Lur Regions, and the Denial of Lur “Peoplehood”

Marxists who emerged in this region, the most prominent of whom were associated with Dr. Azami’s group, active in the 1960s and 1970s, and others after the revolution, largely maintained that the Lurs were not, in the strict sense of the word, a people or a nation. While national demands among Baluch, Turkmen, Kurds, and Turks were recognized, they insisted that others were nations, and the Lurs were not. They accepted national claims for others, yet erased the Lurs. The reasoning was blunt: the Lurs were essentially tribal, and, in their view, a tribe could not claim national rights.

They pursued a pan-Iranist line, perhaps influenced by Stalin’s definition, which treated tribes as something other than nations. Yet Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, societies that were historically tribal in many respects, built their national formations. In this way, the Lur Left contributed little to the early stages of collective national and political consciousness. As a result, many Lur activists today reject and condemn that legacy. The Lur Left did not act because it followed the center's strategy.

Over a broad historical period, nearly every person living in Iran helped generate national movements, articulated linguistic demands, and theorized their own historical narratives. Everyone did this, the argument goes, except the Lurs.

The Islamic Republic of Iran

This section draws on my conversations with my friend, who describes what he sees as an especially severe form of internal colonialism, the extraction of Lorestan’s raw resources, and the hardships that shape daily life there.

Qomrud, A Development Pole Built on Stolen Water

Until the 1960s, Qom was part of Markazi Province and administratively subordinate to Arak. Then, by an ideological calculus, it was set on a path to become a pole of urban development, its status as a pilgrimage city and religious center notwithstanding. From the 2000s onward, and especially since the 2010s, the transformation became visible with striking speed. Qom was turned into a medical hub, among the country’s most well-equipped clinics and hospitals were built there, to the point that people travel from Arak to Qom for treatment. Shi‘a visitors from Iraq also seek care in its facilities, combined with pilgrimage and treatment, and the city’s population has grown rapidly.

Yet, by basic planning logic, Qom lies in an arid zone with limited water resources. There were even estimates suggesting that, within 50 years, Qom and Kashan would face severe water shortages, perhaps leading to an existential decline. Despite this, a major water transfer scheme took water directly from the headwaters of the Dez River near Aligudarz, effectively diverting high-quality water from Lorestan to “develop” Qom.

The grim irony is that many parts of Lorestan remain so deprived that communities receive drinking water by tanker trucks. A massive “water complex,” described by my interlocutor as among the largest in the Middle East, was constructed in the heart of the desert through what he calls large-scale water theft. The Dez is one of the Zagros’s most significant rivers, vital to agriculture, herding, and rural life. Taking water from its headwaters means placing pressure on downstream regions.

A similar story applies to the Karun’s headwaters, diverted toward Yazd, Isfahan, and other arid regions where powerful Persian-speaking elites have historically exerted influence, sustaining industrial and agro-industrial projects there. The Zagros, in this picture, becomes the mother source for all such schemes.

It is worth noting that many of these projects were first conceived under the monarchy as development and infrastructure plans, later pursued aggressively under the Islamic Republic, especially during the Rafsanjani era, and culminated in the boundless dam-building launched under the banner of “reconstruction.” In Lur-inhabited regions, including Bakhtiari areas, as well as in Arab-majority regions and elsewhere, the water crisis has become severe. No one planned for this; the assumption seemed to be that water would always flow, that it would never end. This structure is deeply vulnerable to economic and climatic shocks.

Many of Lorestan’s roads were built in the Pahlavi era, but their primary purpose, my interlocutor argues, was military access and control, not economic integration. Land reform shattered traditional arrangements but did not offer an effective replacement. The result was predictable: poverty, migration, stagnation. The Islamic Republic’s project, in this view, is the continuation of a Reza Shah-era model, now compounded by new crises.

After the 1979 revolution, it was widely assumed that deprived regions like Lorestan would be prioritized. Instead, patterns suggest the persistence of centralization, decision-making concentrated in Tehran, the capital, and industry disproportionately allocated to Persian-majority regions. A rentier economy and the absence of durable investment have become defining features of Lorestan. Industrial projects were either never completed, or remained half-built, or factories shut down after a few years. This is the familiar cycle of “projects inaugurated but never truly operational.”

Concluding Note

The construction of a single “Iranian nation,” or nation-building in Iran, has imposed an enormous cost on non-Persian peoples. These communities, the argument here insists, cannot be asked to submit once again to the same vicious repetition. They cannot be expected to replace one corrupt, ineffective, extractive regime, stained with blood, with another regime that has already proven itself.

The history of the Lurs, like that of other non-Persian peoples, is saturated with catastrophes inflicted on them by the Pahlavi state. The puzzle is that this same regime, or its supporters, has managed, in an oddly effective way, to manipulate the historical memory of a significant portion of the Lurs, so that the massacre of their own people is minimized and the butchers of Lorestan are forgiven.

This essay is an attempt to revive that blood-soaked past and to warn the Lurs that forgetting and forgiving are not permitted. The future must be built on learning from the past, by discarding both the Sheikh and the Shah, and by recognizing national, linguistic, and economic, political, cultural, and ecological justice.

References (as listed in the Persian original)

- John Foran, Fragile Resistance: The History of Social Transformations in Iran from the Safavids to the Years after the Islamic Revolution, trans. Ahmad Tedin, Tehran: Rasa Cultural Services, 1998 [1377].

- Roman Rosdolsky, Engels and the “Non-Historical Peoples”, trans. Forough Asadpour and Mohammad Ebadi-Far, Prometheus Myth Publishing.

- The Past Is the Guiding Light of the Future: Iran Between Two Coups, 1921–1953, Jami Publishing, Ferdin, 1983 [1362].

- Kaveh Bayat (ed.), Operations in Lorestan.

- Iraj Rudgar-Giya, Iran, from the Coup of 21 February 1921 to the Fall of the Shah, Pardis Danesh, 2020 [1399].

- William O. Douglas, Strange Lands and Friendly People, trans. Fereydoun Sanjari, Gutenberg, 1998 [1377].

- Hossein Makki, Twenty-Year History of Iran, Vol. 6, “The Continuation of Reza Shah’s Dictatorship…,” Naser Publishing, 1984 [1363].

- Richard Tapper, “Reza Shah and the Making of Modern Iran,” in Stephanie Cronin (ed.), State and Society under Reza Shah, trans. Morteza Saqebfar, 2004 [1383].

© Copyright IranDraft