Nationalism, War, and Affection for One’s Homeland

A sense of belonging to one’s home is a human feeling; it does not inherently require allegiance to any particular state or fixed borders. Home is where you work, toil, build a life and a house.

Elham Hoominfar

August 9, 2025

“Iranists” Against Iran

During Israel’s twelve-day war against Iran, many of those who had long accused the left, feminists, and advocates for the rights of Iran’s ethnic nationalities of being “unpatriotic/disloyal” (بیوطن) — those who routinely dismissed even the most basic demands of these groups as “separatism” (تجزیهطلبی) and never tired of chanting “preserve territorial integrity” (حفظ تمامیت ارضی) — suddenly stood shoulder to shoulder with a foreign aggressor.

They tethered their notions of “homeland” (وطن) and “nation” (میهن) to one of the most lethal states on earth, a country with a documented record of war crimes, genocide, and ethnic cleansing — and one that makes no secret of its willingness to see Iran partitioned if it serves its survival. These self-proclaimed “Iranists/Iranophiles” danced under the flag of Israel in celebration of an assault on their own country.

Foremost among them was the exiled crown prince, Reza Pahlavi, who dreams of ascending to the throne with the help of Israeli and American military intervention. After the assassination in Washington of a young Israeli couple who worked at their country’s embassy, Pahlavi issued a condolence message, but has never once extended such sympathy to the families of Iranian civilians or conscripted soldiers killed in Israel’s attacks. Many of these Iranian victims, it was later proven, had no ties whatsoever to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The openly feudal relationship between the Israeli state and Reza Pahlavi now leaves no room for pretense. In a recently released program titled Emergency Phase Booklet (دفترچه دوران اضطرار) — link — Pahlavi called for Israeli security agencies to oversee Iranian institutions, ostensibly to “prevent sabotage,” provide “institutional and security training,” “transfer knowledge to law enforcement, intelligence, and border protection agencies,” and enable “cyber, intelligence, and judicial cooperation.” In other words, the security apparatus of Iran would be organized and directed under the close supervision of Israeli security operatives.

From the outset of his exile, Pahlavi and his affiliated organizations have depended on foreign funding, from covert CIA support in the 1980s, to a profligate and ill-conceived multi-million-dollar Israel–Saudi coup plot, to official U.S. government democracy-promotion budgets in the 2000s, and financial backing from networks tied to the late American–Israeli billionaire and pro-Israel powerbroker Sheldon Adelson. Reports in reputable American, Israeli, and European outlets paint a clear picture of Pahlavi’s decades-long financial dependency on foreign states and lobbying circles. (1) [See Endnote 1]

The Islamic Republic as “Nationalist”

On the other side of the coin is the Islamic Republic of Iran, which, in the wake of its war with Israel, abruptly began draping itself in nationalist symbols. Overnight, the regime that had built its identity on being “Islamic”, founded by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Shiʿa cleric who never hid his disdain for the words “national” (ملی) or “nationalism” (ملیگرایی), discovered the uses of nationalism when its own survival was at stake.

From a giant billboard in Tehran’s Vanak Square depicting the mythical archer Arash Kamangir wrapped in the green Shi’ite religious scarf of Abolfazl, to state-sanctioned singers performing the patriotic anthem “Ey Iran” (ای ایران), the theocratic state suddenly began to market itself as the custodian of not Islam but the nation.

How can a theocratic system whose official ideology is Islamism, whose legal structure is ruled by Islamic law (شرع), and whose constitution recognizes the absolute authority (ولایت مطلقه) of a Shiʿa jurist as the country’s supreme leader, turn to an ideology that is, at least in form, secular? Why did the Israeli military assault, which triggered twelve days of war, convince the Supreme Leader that his most vital tool for rallying popular support was the anthem “Ey Iran”? Was this simply a cynical survival tactic, or is there a deeper, underexplored relationship between Islamism and nationalism?

I am not here to revisit the classic definitions of nationalism or the history of the ideology in detail. The formation of the “nation-state” (دولت-ملت) has, everywhere, almost invariably involved some form of nationalism. In Iran, most historians date the formation of the modern national state to the post-Constitutional Revolution era, roughly concurrent with the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah Pahlavi established the first centralized modern and secular nation-state in the early 20th century.

Until the so-called Islamic Revolution of 1979, which toppled the Pahlavis, various strands of nationalist ideology were promoted both by the monarchy and by its opponents, from the National Front (جبهه ملی), the Third Force (نیروی سوم), and the Iran Party (حزب ایران) to the Freedom Movement of Iran (نهضت آزادی), the Pan-Iranist Party (حزب پانایرانیست), and others. Among the anti-Pahlavi camp, Mohammad Mossadegh, leader of the oil nationalization movement, embodied the emotional and political weight of the word “national” more than any other figure. For his part, Mohammad Reza Shah also sought to project himself as a nationalist, competing with Mossadegh’s legacy and positioning himself as a leader of oil-exporting nations who defended Iran’s economic sovereignty against Western dominance.

We might say that post-Constitutional Iranian nationalism has appeared in two main forms: authoritarian nationalism (پهلویسم) and liberal nationalism (مصدقیسم), along with their offshoots. Throughout the Pahlavi reign, as far as my research shows, no Islamist political movement formally raised the banner of nationalism. Even in the Freedom Movement of Iran, a prominent national-religious organization that emerged after the National Front, leading clerics such as Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani participated, but the movement’s public image was not overtly Islamist. Figures like Mehdi Bazargan tried to modernize Islamic thought in line with contemporary science.

The Islamists who would go on to found the Islamic Republic were hostile to both nationalism and secularism. Their intellectual lineage runs from Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri during the Constitutional Revolution to Ayatollah Boroujerdi and Khomeini himself; from the terrorist group Fada’iyan-e Islam (فدائیان اسلام) to the Hojjatieh Society (انجمن حجتیه) and the hardline Islamic Coalition groups (هیأتهای مؤتلفه) backed by the traditional merchant class. None of these movements had any pretense of “Iran-love” in the nationalist sense; their declared enemies were the West, Westernization, the “immoral” Shah, and women’s emancipation. The observance of Sharia and the establishment of religious schools were always their chief political platform. These were the founding fathers of the Islamic Republic.

During the eight-year Iran–Iraq War, the emphasis was never on the concept of “nation” (ملت) but on the “Army of Islam” (سپاه اسلام) and the religious mission. There is no writing, sermon, or speech by Khomeini in which “Iran” as a homeland (وطن) occupies a place above “dear Islam” (اسلام عزیز).

What happens when Islamist forces capture the secular structures of a nation-state? At first glance, it looks like a glaring contradiction. In rejecting the secularism of the Pahlavi era, the Islamic Republic institutionalized Sharia and gender apartheid. On women’s rights, personal freedoms, and openness to the modern world, the Pahlavi monarchy and the Islamic Republic stand as opposites.

To erase the Pahlavi legacy from public memory, the Islamic Republic’s leadership denigrated and downgraded national holidays such as Nowruz and Yalda, purged Iranian historical figures and pre-Islamic heroes from the official pantheon, and shifted the education system from “Iranian” to “Islamic.” The state funneled its largest budgets and resources into Shiʿa ceremonies and Islamic propaganda.

Yet — and this is the point I want to stress — capturing the bureaucratic, military, and security apparatus of a centralized modern nation-state has historically led to similar behaviors and policies, regardless of ideology. The features that define Iranian nationalism go beyond ancient symbols and festive rituals: they include an emphasis on Persian linguistic unity (وحدت زبانی فارس), territorial integrity (تمامیت ارضی), and strategic depth defense. The repression of non-Persian nationalities and the drive to assimilate them into the dominant culture, to better control the central state, is another core feature.

On these points, the Pahlavi monarchy and the Islamic Republic have acted in the same way. When the current Supreme Leader, after the twelve-day war, swapped out mourning chants for the anthem “Ey Iran,” it was simply another expression of the central state’s nationalist ideology, this time wielded as a tool to stir patriotic sentiment in service of its political and military aims. Pahlavi and the Islamic Republic alike are mixtures of zealotry, populism, and chauvinism: one fancies itself the leader of the Islamic world; the other dreams of ruling over a mythical “Aryan Iran-Shahr” (ایرانشهر آریایی).

Media as a Tool for Mind Manipulation and Systems of Repression

With the rise of the revolutionary movement Women, Life, Freedom (زن، زندگی، آزادی), many Persian-language media outlets abroad began the process of “leader manufacturing.” These were leaders with no organic connection to the heart of the movement. Figures such as Reza Pahlavi and Masih Alinejad—whose financial dependence on foreign institutions is well documented—were among those elevated by these outlets. They had no genuine ties to the popular uprising and openly endorsed military intervention for regime change, unashamedly speaking of “cutting off the snake’s head in Tehran.”

These self-appointed leaders were, by nature, in direct conflict with the demands of Iran’s progressive grassroots movements. They were the products of media platforms that, lacking a critical approach, and sometimes driven by financial incentives or professional ignorance, sought to manipulate public opinion.

It is no exaggeration to say that a significant portion of these outlets have abandoned their core mission: to provide the public with independent, transparent information. If the Islamic Republic suppresses the free flow of information through censorship and intimidation, these other outlets pose a different kind of threat, by distorting reality and promoting falsified narratives that undermine public awareness.

Media scholars such as Walter Lippmann (2) and Harold Lasswell (3) have long stressed that media are not merely mirrors of reality; they actively shape it. By selecting topics and framing coverage, they guide public thought. In capitalist societies, media are not just tools for informing the public; as Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky (4) demonstrated in Manufacturing Consent, they operate within a propaganda model, filtering information, shaping stories, and reproducing the interests of political and economic elites. The result is the manufacture of the “consent” necessary to perpetuate dominance.

Inside Iran, state-run media under the control of the regime’s repressive apparatus may have wielded influence in the early decades of Islamist rule. Today, however, they have largely lost the ability to mold the public’s consciousness in line with their own interests.

By contrast, the role of Persian-language outlets abroad, most notably Iran International and Manoto, in shaping public perception is striking. Through idealized portrayals of pre-revolutionary Iran (a nostalgia for a “golden age” that never truly existed), constant reinforcement of the idea that ordinary Iranians are powerless to change their situation, and repeated insistence on the necessity of foreign intervention or global sanctions, these outlets have served the interests of their financial backers. Despite their repeated claims of commitment to the free flow of information, they have yet to disclose the true sources of their funding or the identities of their ultimate patrons.

These undemocratic platforms, by nurturing the illusion of a “foreign savior,” elevating the son of the former dictator as a supposed alternative for the post–Islamic Republic era, and reproducing narrow, self-serving narratives, have not only misled segments of the public but have also managed to sway those without access to critical education or independent analysis.

Between Repression and Bombardment: Lived Accounts from Iran

On the second day of Israel’s military assault on Iran, several friends inside the country, people I knew well, who had been impatiently waiting for a foreign savior, suddenly experienced the terror of war up close. The dream of liberation at Israel’s hands turned into a nightmare. Overnight, the romanticized version of war promoted by Persian-language diaspora media collapsed.

On the first day of fighting, I wrote on Facebook: “In the morning, the Islamic Republic executes our people; at night, Israel bombs them”, and posted several photographs of destroyed homes. One dear friend, a fellow activist inside Iran, sent me a private message: “These houses don’t belong to the people, they belong to the people’s killers. Israel is pure evil, but I’m glad it’s targeting IRGC (سپاه) forces. Haven’t they killed enough of our people?” My friend, too, had fallen for Israel’s myth of “precision strikes.”

A few days later, after hearing nothing from her, I saw she had reappeared on social media, writing about a nightmare she had endured. I messaged her again to ask how she was. She replied: “We’re still alive… It was a real nightmare. If the Islamic Republic doesn’t kill us, Israel will finish the job.”

I can understand this paradoxical feeling among some Iranians. Let’s return briefly to examples of repression during the Women, Life, Freedom (زن، زندگی، آزادی) uprising: one widely shared video from Tehran’s Ekbatan neighborhood showed a group of Basij (بسیج) militiamen swaggering through the streets, shouting threats, boasting about their power in Syria, and brandishing weapons and batons as they prowled for unarmed “enemies.” Images of brutally killed civilians, many of them children and teen agers, flooded social media.

In one harrowing scene, the family of 9-year-old Kian Pirfalak in Izeh, desperate to preserve their child’s body, begged neighbors for chunks of ice. Reports surfaced of gang rapes in prison against detained women, men, and even children. Justice has been absent for over four decades. Under such circumstances, it is hardly surprising that people feel no sympathy for the deaths of killers and rapists who targeted their children.

One of Israel’s bombing targets was the headquarters of IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, صدا و سیما), for nearly 45 years the regime’s propaganda arm and a key pillar of its theocratic machinery. It was the same institution that broadcast coerced confessions from political prisoners, often under visible duress and humiliation; the same place where Sepideh Rashno, arrested for refusing compulsory hijab, was tortured and forced to repeat a scripted statement on camera. This is a media apparatus that institutionalized lies, inverted reality, and fueled hatred.

Yet under international law, attacking media facilities, even those complicit in authoritarian propaganda, can be considered a war crime. IRIB’s main building is also a notable example of modern Tehran architecture. It was not brought down by the hands of Iranian protesters, but by a foreign military force.

While Iranian society desperately needs a collective reckoning with these very real paradoxes, one comment from a women’s rights activist I spoke with struck me deeply: “We know exactly what IRIB is. But I wish that building hadn’t been destroyed by another criminal. I wish our own people had seized it.”

A close relative sent me a video from near his home in eastern Tehran, showing a house belonging to an Iranian nuclear scientist. He said: “This is one of several homes destroyed. Look at how many innocent people were killed here, women, children, people who were just neighbors. No IRGC forces, no commanders, just a nuclear scientist. These are the country’s assets. And even if he had been Basiji or IRGC, should his innocent child have been killed? Should his neighbors have been wiped out with him?”

After the attack on Evin Prison, a friend in Tehran told me angrily:

“Apparently the monarchists told Israel to hit Evin so prisoners would be killed, the people would flood the streets, and that man could become king! Yes, we aren’t free, and the Islamic Republic is a dictatorship, but is the plan to save us by killing us? All these protests and uprisings are against the Islamic Republic because it kills us, takes away our freedom, and ruins Iran. And now you want to ‘liberate’ us by waging war, by killing my neighbor, by destroying our homes?!

Patriotism, the Sense of Belonging to Home and People

“Homeland” (وطن) and “nation” (میهن) are broad, imprecise concepts, usually bound up with a human’s attachment to the place where they were born and raised, and where their memories and identity are rooted. States have always manipulated these emotions for their own ends.

A sense of belonging to one’s home is a human feeling; it does not inherently require allegiance to any particular state or fixed borders. Home is where you work, toil, build a life and a house. It is where you form friendships, love, and family; where familiar faces meet and mutually acknowledge one another’s dignity.

The formal, legal concept of citizen, the nationality assigned by a state, is not the same as the emotional connection to “home” or homeland, yet in modern life it becomes necessary in order to access certain material and economic rights. These rights are defined by citizenship in a given country. But homeland is not defined by the authority of governments or the ruling class; it is defined by attachment to the place we live and by the peaceful coexistence of nationalities and social groups side by side.

In politics, patriotic feeling has rarely been linked to the environment. A liberatory ecology focuses on changing the structures that dominate both humans and nature. Social emancipation, environmental justice, and structural transformation go hand in hand. And the environment I speak of recognizes no borders and carries no passport from any “nation-state” (دولت–ملت).

The so-called “Iranists/Iranophiles” (ایرانگرایان) who are in fact anti-Iran, place blind trust in a foreign aggressor, indifferent to environmental destruction and human life, willing to sacrifice even their ancestral land and fellow citizens for a mirage called “Imperial Iran”, in truth, a return to monarchical domination.

Aggressor states and their war advocates show no concern for the environmental consequences of conflict: not for human lives, nor for the destruction of infrastructure and natural resources, nor even the risk of nuclear contamination from strikes on atomic facilities. In their willingness to destroy Iran and its people, these pseudo-patriots have little to distinguish them from the Islamic Republic.

By contrast, time and again, in the hardest moments, it is the marginalized, the dispossessed, who have stood at the forefront of solidarity and resistance. We have seen clearly that in defending what they call “home,” Iran’s ethnic groups, often smeared as separatists, have been on the front lines: quietly, consistently, and with resilience.

Just last week, a sobering reminder surfaced: over the past few years, more than ten Kurdish environmental activists have died fighting wildfires in western Iran, among them Mokhtar Yasemin, Yasin Karimi, Belal Amini, Sharif Bajour, Omid Kohneposhi, Rahmat Hakiminia, and Mohammad Pazhouhi, Hamid Moradi, and others. Many of these deaths occurred in remote, rugged terrain, without adequate equipment, sometimes amid claims of landmines left from the Iran–Iraq war or of fires deliberately set by military forces. These activists were often part of grassroots groups like the Chiya Green Association (انجمن سبز چیا) or Zhivay Paveh (ژیوای پاوه), volunteer efforts without state support. Kurds, Turks, Baluch, Arabs, Lors, Gilaks, and others have long resisted the central government in defense of their land and home, only to be branded traitors or separatists by the nationalist establishment.

Setting aside a few ethnic chauvinists, the prevailing attitude among Iran’s nationalities toward homeland and home is not drawn from the decayed ideology of nationalism, whether the dominant or the subordinate kind. As the Arab-Iranian sociologist Aqil Daghaqleh noted to me: “As I predicted, after the outbreak of war, a substantial portion of Arabs inside Iran, if not the outright majority, have stood against the war and alongside other Iranians against Israel.” With bitter irony, he adds: “Apparently, those centralist Persians who have always accused us of separatism have now themselves become supporters of war and the breakup of Iran.”

Sevil Soleimani, a sociologist and feminist, told me: “I am a staunch opponent of Israel’s policies on Gaza and the occupation. But today’s war is not just about Israel for me. Even if Azerbaijan, my own flesh and blood, or Turkey were to attack Iran, Tabriz, or Urmia, I would stand against them just as I stand against Israel. Frankly, if a Syria-style war started in Iran, I would be ready to return home and defend it. Defending home is different from anything else. I cannot watch my country’s people, our families, be killed so that a few Pahlavi loyalists, with foreign help, can return and rule.”

She adds: “From the moment a bomb fell near our home, this war became my war. These ruined buildings, these bombed-out roads, they are for the people.”

Soleimani continues: “I didn’t just weep for Tabriz; I wept for Kermanshah and Tehran too, and that has nothing to do with nationalism or patriotism. Because I have wept as much, perhaps more, for Gaza. My heart burns more for Gaza than for Iran, because they are even more defenseless than we are.”

A friend from Kermanshah, active in numerous Women, Life, Freedom protests, has sent me photos and updates throughout the war whenever the internet allowed. One comment of his still echoes in my mind: “What Israel is doing runs counter to the interests of our nation and our social movements. They want nothing but a weakened Iran. The separatism they’re pushing would only drag us into a civil war, keeping us permanently divided and making any deep change for the benefit of all Iranians impossible.”

Homeland or Death, We Shall Win (5)

The wife of Reza Pahlavi, apparently so intoxicated by dreams of becoming the Iranian Queen that she has lost all restraint, posted a shameful message on social media during the days when we were worried sick for our homes, families, cities, and neighbors. She cheered on the foreign aggressor, applauding and shouting, “Israel, hit them! You’re doing great!”

In the face of such humiliation and indifference from so-called “Iranophiles” toward the lives of Iranians, other images stand out: a man playing the violin in the streets of Tehran amid smoke and the sounds of bombing; another handing out drinks with his young daughter to people standing in long lines for fuel. They become living tableaux of resistance.

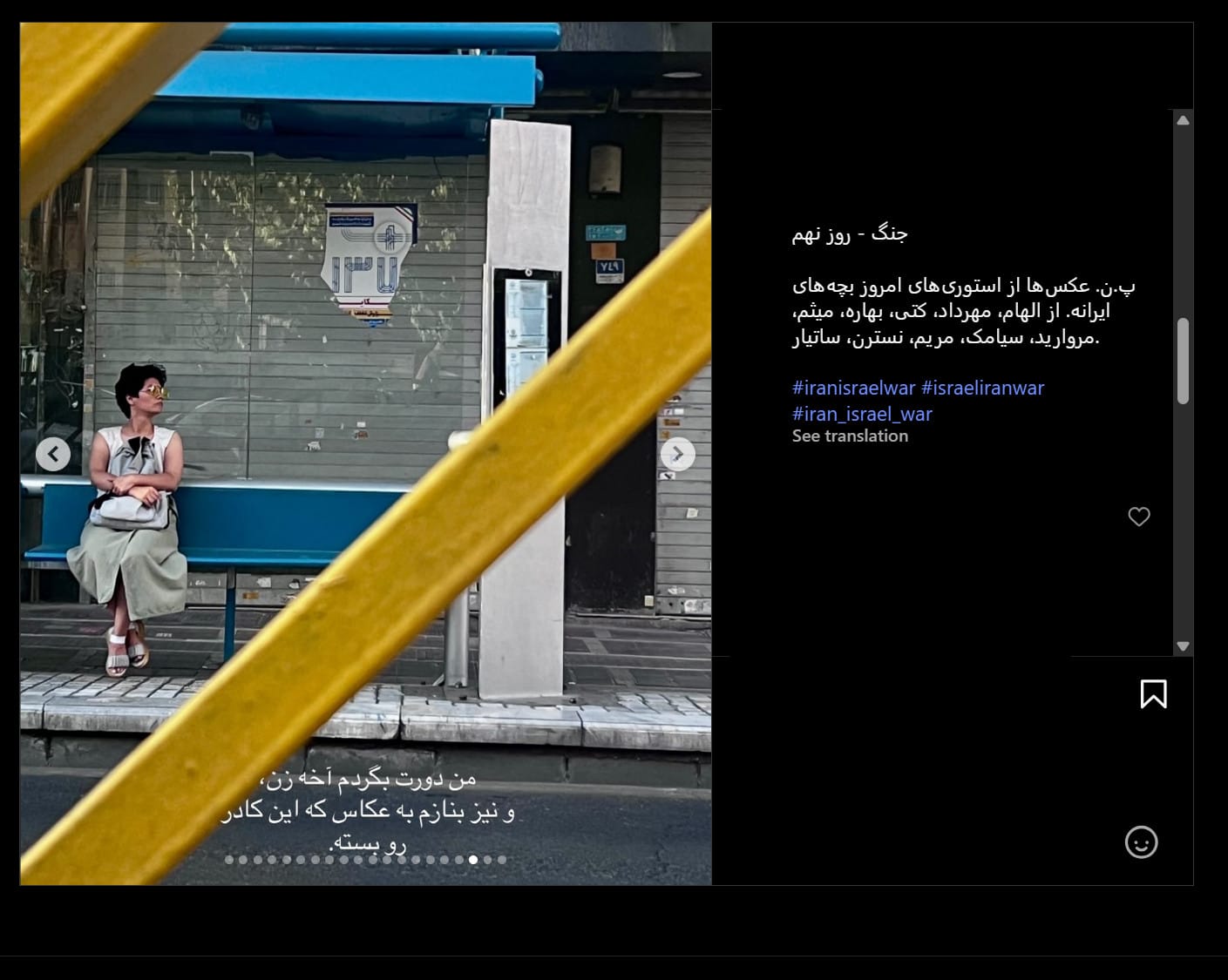

A woman in defiant, non-Islamic dress, embodying the spirit of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, sits at a bus stop: unbent, self-possessed, unmoved by the Islamic Republic’s domestic oppression or by the bombs of a foreign enemy. And I recall again the symbols and acts of resistance in this revolutionary movement, which some mistakenly think has ended.

And our homeland is precisely this: the place where women and men resist every form of domination.

When Marx (6) or Lenin (7) spoke of the working class having no country and rejected bourgeois nationalism, they did so in the context of power structures and ruling classes willing to trade away our lives, water, soil, and very existence for their own gain. My definition of attachment to home or homeland is the opposite of what authoritarian nationalists mean by the word “nation.” This is why they so easily surrender the field to another form of domination.

Some revolutionaries go even further in nurturing a genuine love for homeland. For Che Guevara, homeland is not defined by soil, ethnicity, or race, but as a space where love and the struggle for humanity converge. “A true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love,” he once said.(8)

Homeland means people, justice, language, culture, and resistance to oppression, not political borders or a government’s flag. Homeland is the arena of struggle for liberation. And it is precisely for this reason that war is not only a physical threat but a profound threat to that arena itself, the same arena in which we have fought for years, and which, at its height, has become the revolutionary Women, Life, Freedom movement. Now, this movement faces a new danger: one of the most aggressive foreign states in the region.

The Islamic Republic, until now the sole repressive force over the Iranian people, has found a rival, one that threatens the same arena of resistance from outside through military aggression.

Homeland is the people. But for authoritarian nationalists, “homeland” is a past mired in the hereditary nostalgia of the ruling class, a past defined by war, bloodshed, and repression, whether in the form of royal dynasties or destructive religious ideologies. Defending the homeland means defending its people, its environment, its minorities, and social justice. This vision rejects the denigration or threat of other peoples and opposes cultural supremacy.

The working class has no homeland because “homeland” has been turned into a tool of class domination. Workers are duped into sacrificing their lives for the interests of the ruling class; their social consciousness is manipulated, and “nationalism” becomes an ideological weapon. In reality, the homeland is the oppressed themselves. That is why we stand with Palestine, just as we care for Tabriz, Tehran, Rasht, Kermanshah, and every village and city in Iran, as well as the people of Sudan and Ukraine.

The kind of nationalism that builds walls between us and puts borders ahead of human life is a dangerous ideology. It does not nurture belonging to home but venerates boundaries used to demean Afghans, to stoke war, and to create enemies out of Arabs and anyone labeled as “other.” Nationalism is an army of repression, one that targets our rights to nature, our private lives, our mother tongues, our biodiversity and cultural diversity, our gender equality, and our social justice.

Rosa Luxemburg once said (9) that war is an imperialist, not a defensive, phenomenon. Modern wars are not fought to protect people or homeland, but for control and domination. In her view, a true socialist does not support war and cannot choose between two evils; instead, they must work to transform it into social revolution.

That is why we stand with the Women, Life, Freedom movement, not with the invasion of a foreign aggressor, nor with the repression of a domestic tyrant. We want freedom to emerge from society itself, not through war or foreign intervention.

The Israel–Iran war is a confrontation between two structures of power and repression, not a people’s war. But when war targets our lives and destroys our cities, we will seek a way to stop it, guided by our own traditions of resistance. The peoples of the region cannot rely on their governments for peace or justice. And as Lenin said: “Not one word for war, not one coin for armaments.”

Freedom will not come from foreign bombing campaigns or U.S. sanctions, but from within society and through popular organization. To rely on Israeli warplanes or American sanctions is not patriotism, it is the reproduction of modern servitude.

Homeland is not merely soil and flag, but people, freedom, justice, and true independence. From this perspective, inviting foreign attack, even to topple a repressive regime, is not an act of patriotism but a form of collaboration with the machinery of global war and a betrayal of homeland and people.

--

Elham Hoominfar is an assistant professor in the Global Health Studies Program at Northwestern University. Hoominfar is a sociologist whose research expertise focuses on intersections of environment and society and understanding of social inequalities and social movements with an interdisciplinary approach.

ENDNOTES

- Financial Resources and Support for Reza Pahlavi (1980–present)

U.S. Government and CIA Support

- CIA Funding in the 1980s: Multiple sources indicate that the CIA provided financial support to Reza Pahlavi during the 1980s, in the early years of his exile. A New Yorker report in 2006 (“Exiles” by Connie Bruck) first asserted that Pahlavi received CIA funding in the 1980s, which, according to the Washington Institute, “strengthened the popular belief” that he depended on U.S. backing. (The exact amounts are not publicly disclosed in these reports.)

o https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/03/06/exiles-6

- Mid-2000s Democracy Promotion Funds: In the mid-2000s, the U.S. government openly budgeted tens of millions of dollars to support Iranian opposition groups (including media broadcasts and dissidents aligned with Pahlavi’s cause). In 2006, the Bush Administration requested about $75–$85 million for “democracy promotion” in Iran – funding Persian-language broadcasts (Voice of America TV, Radio Farda) and grants to NGOs and human rights organizations working on Iran. While officially for civil-society and media, this infusion was widely seen as benefiting prominent exiles; indeed, Pahlavi and his supporters welcomed President Bush’s hard line and engaged U.S. officials around that time. In 2007, for example, President Bush even met privately with a couple of Iranian dissidents (including one of Pahlavi’s associates) during a conference in Prague, a symbolic show of support.

- Funding for Opposition Media: U.S. lawmakers also pushed direct support for Iranian opposition media that bolstered Pahlavi’s royalist message. Notably, in 2003 Senator Sam Brownback introduced an amendment to set aside $50 million to fund Iranian opposition broadcasters in Los Angeles – TV and radio stations run by exiles, “most of which promote a restoration of the Shah’s monarchy” – as well as related pro-democracy groups. (This was reminiscent of how Washington had funded Iraqi exile media before the Iraq War.) Such U.S. funding initiatives, overt and covert, reinforced perceptions that Pahlavi’s activities were bankrolled by Washington, even as U.S. officials claimed the goal was supporting democracy rather than regime change.

1982 Israeli and Saudi-Backed Coup Attempt

One dramatic episode of foreign support was a now-known 1982 coup plan involving Israeli, American, and Saudi partners to restore the monarchy in Iran. According to an investigation by journalist Samuel Segev (reported in the Los Angeles Times):

- In 1982, Israel’s then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon and CIA Director William Casey secretly approved a plot to overthrow Ayatollah Khomeini and install Reza Pahlavi or another monarchist figure in power. Sharon agreed Israel would supply $800 million worth of arms and military training to Pahlavi’s supporters for the attempted coup. Wealthy Saudi middleman Adnan Khashoggi facilitated promised Saudi financing for the operation, even securing an arrangement to use Sudan as a staging ground (Sudanese President Jaafar Numeiri agreed to host training bases in exchange for $100 million).

- This ambitious plan had high-level backing – the L.A. Times notes it “had the approval of the late CIA Director William Casey” – and brought together figures like Yaakov Nimrodi (an Israeli ex-intelligence officer and arms dealer) and Saudi royals via Khashoggi’s connections. Reza Pahlavi himself initiated contact with Nimrodi after hearing his call for Khomeini’s ouster on BBC radio, inviting him to meet and germinating the coup idea. However, the scheme collapsed before execution: in late 1982 Sharon was forced to resign (after the Sabra and Shatila massacre scandal), and his successors in the Israeli government backed away from the plot. Without Israeli leadership, the plan died. In sum, this episode shows that Israel (with tacit CIA and Saudi agreement) was ready to invest huge resources – hundreds of millions in arms – to help Reza Pahlavi retake Iran, although ultimately no coup materialized and Pahlavi did not receive those arms funds once the plan was shelved.

Western Private Donors and Allies (e.g. Sheldon Adelson)

Beyond government assistance, wealthy private individuals in the West have given moral and possibly financial support to Reza Pahlavi and his organizations:

- Sheldon Adelson (American casino magnate) – Pahlavi cultivated relationships with hardline pro-Israel and neoconservative circles in the U.S., including figures like the late Sheldon Adelson. Adelson was a billionaire GOP donor known for funding hawkish anti-Iran causes, and Pahlavi moved in the same circles. In the 2000s and 2010s, Pahlavi met with Adelson and attended pro-Israel events associated with Adelson’s network. (For instance, Pahlavi quietly met Israeli officials and addressed groups like JINSA and WINEP, think-tanks backed by pro-Israel donors.) Adelson himself poured money into organizations that align with Pahlavi’s agenda – he underwrote the Israeli-American Council (IAC) and the Zionist Organization of America, among others, which have collaborated with Pahlavi’s allies in the diaspora. This indirect funding bolstered Pahlavi’s platform: for example, an Iranian-American group linked to monarchists received State Department grants to run anti-regime social media campaigns, and it had ties to IAC/ZOA circles funded by Adelson.

- Adelson’s stance: While Adelson’s money supported the broader ecosystem of Iran regime-change advocacy that Pahlavi benefits from, Adelson’s personal view of Pahlavi was mixed. In 2007, at a Prague conference of dissidents, Adelson spoke with an Iranian activist and voiced skepticism about Reza Pahlavi, complaining that Pahlavi “doesn’t want to attack Iran.” Adelson favored more militant exiles – he said he preferred someone like exile Amir Abbas Fakhravar, who openly welcomed U.S. military action, quipping “if we attack, the Iranian people will be ecstatic”. This suggests Adelson was not directly bankrolling Pahlavi’s own group at that time, since Pahlavi’s strategy was less explicitly militaristic. However, by the late 2010s Pahlavi did align more closely with Adelson’s hardline positions – he endorsed President Trump’s “maximum pressure” sanctions and even adopted the slogan “Make Iran Great Again” in support of Trump, while joining pro-Israel rallies during the 2023 Israel–Hamas war. In effect, Pahlavi positioned himself in line with Adelson’s worldview, and his exile campaign drew on funding and platforms provided by Adelson-backed groups (even if Adelson didn’t hand him money outright).

- Other Wealthy Supporters: Aside from Adelson, reports suggest Pahlavi has relied on wealthy supporters among the Iranian diaspora and sympathetic foreigners. Iranian monarchist expatriates in the U.S. (including some affluent Iranian-American businessmen and the Iranian-Jewish community in Los Angeles) have donated to his cause over the years. (By his own admission, Pahlavi has “never had a job” and lives on his family inheritance plus donations from loyalists in the West.) Furthermore, Pahlavi has maintained a “long-term relationship with Israel and the Israel lobby” in Washington. For example, he met privately with Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu and others in the early 2000s, and in April 2023 he was officially hosted in Israel by Netanyahu’s government as a distinguished guest – a sign of political support from Israel. While no direct dollar figures were publicized around that visit, analysts noted that Israel was effectively endorsing Pahlavi as the face of Iranian opposition and likely offering behind-the-scenes assistance.

In summary, Reza Pahlavi’s exile activism since 1980 has been sustained by a network of foreign funding and donations. U.S. intelligence and democracy-promotion programs gave him an early boost in the 1980s and mid-2000s. There was even a major (abortive) investment by Israel (with U.S. and Saudi concurrence) in 1982 to arm his followers with $800 million in weaponry for a hoped-for counterrevolution. In later years, he benefited from American taxpayer-funded grants to Iranian dissident media and from the patronage of hawkish billionaires like Sheldon Adelson who funneled money into anti-Iran advocacy organizations that embrace Pahlavi’s agenda. All these reputable reports – from newspapers, magazines, and policy journals – highlight how Pahlavi and his affiliated groups have depended on foreign financial support (mostly American, Israeli, and to some extent Saudi) rather than domestic Iranian resources.

- Lippmann, W. (1922). Public Opinion. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- Lasswell, H. D. (1927). Propaganda Technique in the World War. New York: Knopf.

- Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Homeland or Death — We Shall Overcome: Main slogan in the Cuban Revolution, emblem of anti-imperialist resistance.

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). Manifesto of the Communist Party. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm

- Lenin, V. I. “The proletariat has no country.” https://marksizm.org.tr/?lang=en&p=5056

- Anderson, J. L. (1997). Che Guevara: A revolutionary life. New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Luxemburg, R. (1915). The crisis in the German social democracy (The Junius pamphlet), Ch. 7. https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1915/junius/ch07.htm