Power and Shi‘a Theocracy in Iran

Editorial Note (2026):

In the wake of the popular protests in Iran in January 2026, public curiosity about the nature of the Islamic Republic, its political architecture, and its internal logic of power has intensified. The essay below, first published in Persian in 2013, is drawn from the archives of Abdee Kalantari, an Iranian Marxist author. It examines the Islamic Republic not as a deviation or aberration, but as a coherent, if deeply reactionary, political system, one whose inner mechanisms remain largely intact.

I. A Populist Revolution and the Normalization of Emergency

The Revolution of 1979 in Iran was, in the full sense of the word, a revolution, populist in form and content. Like all revolutions, it produced a prolonged condition of extra-legal power, a state that defined itself for years through “emergency,” exception, and urgency. After the fall of the monarchy, power did not originate from a single source, yet all competing forces rode the wave of a mass popular movement and converged, temporarily, under the charismatic leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini.

Charisma here meant spiritual authority lodged in the emotional and symbolic universe of the masses, a devotion whose logic was fundamentally irrational. From the outset, the revolutionary order defined its emergency condition as maslahat-e nezam, the expediency of preserving the system. This was not a temporary deviation but a constitutive principle of political theology, one that allowed the suspension of legality, the institutionalization of friend–enemy distinctions, and the division of society into insiders and outsiders, all justified in the name of survival, until the crisis passed, or until the ruling power bloc consolidated itself.

II. Political Theology versus Shari‘a

The ideology of the Islamic Republic had little to do with shari‘a as a coherent legal or jurisprudential tradition. It emerged instead from political theology, Islam refracted through revolutionary Shi‘ism, anti-imperialist discourse, Khomeinism, the doctrine of the Guardianship of the Jurist, Shari‘ati-ism (teachings of the Islamist author Ali Shariati), and the militant Islamism of organizations like the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK). What took shape was a conservative, religious, right-wing populism.

Law, in this framework, was not a constraint on power but its instrument. Political theology subordinated jurisprudence to survival, legality to expediency, and rights to ideology.

III. The Constitution as Counter-Revolution

Iran’s constitution was drafted by an Assembly of Islamic Experts, overwhelmingly composed of clerics and jurists, acting as the founding body of the new regime. On the command of Khomeini and his closest allies, Ayatollah Beheshti, Ayatollah Motahhari, and Ayatollah Montazeri, the principle of velayat-e faqih was installed as the constitution’s central pillar.

Qur’anic verses were woven directly into the legal framework, while the Guardian Council, composed of Shi‘a clerics, was granted permanent authority to supervise legislation and ensure its Islamic character. In the founders’ political imaginary, citizens were not citizens at all but members of an ummah, and sovereignty belonged not to the people but to the Imam of that collective body.

IV. Canceling Constitutionalism, Installing a Modern Theocracy

Within months of the February 1979 victory, the revolutionary leadership secured popular approval for the institutional blueprint of a modern theocracy. This act effectively annulled the Constitutional Revolution of 1906–11 and erased its legacy. Modern political parties, secular civil society, and Enlightenment-based intellectual traditions were “canceled out,” replaced by an indigenous clerical intelligentsia and the dense organizational network of mosques.

A politics of an entirely different species dismantled the dependent capitalist state apparatus of the Shah and erected in its place a nativist, anti-imperialist, populist theocracy. Clerical fascism, institutionalized as Guardianship, replaced monarchy. This was not a superficial superstructure but an ambitious project of total social reconstruction.

V. Why This Theocracy Is Modern

The Islamic Republic is modern not because it is progressive, but because it subordinates religious doctrine to the rationality of power. From its inception, the regime prioritized the logic of preservation over jurisprudence. This orientation derived directly from Khomeini’s practice as a revolutionary statesman.

While committed to establishing an Islamic government, Khomeini consistently placed the survival of the system above fiqh and tradition. He sought a working equilibrium between dogma and state survival, and to maintain it he had to confront both conservative clerics and revolutionary Islamist leftists.

VI. Governing God with the Instruments of the State

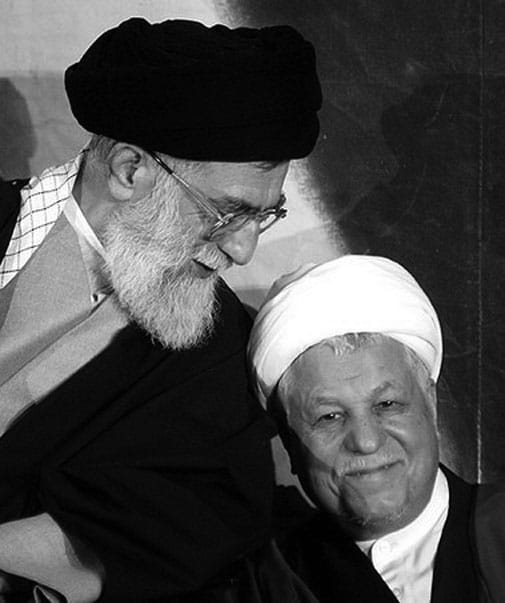

Figures such as Beheshti and Rafsanjani understood this logic. They were modernizing clerics who sought to administer a religious theocracy using the tools of modern statecraft. Without Khomeini’s unique charismatic authority, none of them would have accepted elevating elderly, scholastic grand ayatollahs from medieval seminaries to the pinnacle of political power. Succession, therefore, had to be decided by expediency, not scholarly merit.

VII. How Power Is Exercised

The Guardianship exercises power through three primary mechanisms:

- Shi‘a belief and religious-political culture, internalized by the masses as folklore and ritual.

- Ideological apparatuses, including mosques, Friday prayers, clerical networks, and state media.

- Coercive institutions, notably the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Basij, and informal paramilitary forces.

VIII. Islamization as Social Engineering

Within this framework, Iran’s rentier capitalism and bloated bureaucracy were reorganized under a Shi‘a theocracy. Secular institutions were Islamized from top to bottom, education, law, the military, public morality, mass media, civic consciousness, and above all the regulation of women’s bodies and visibility.

The promised society of the oppressed and the barefooted, the justice of Ali, was held out as an ideological horizon, while a new subjectivity hostile to modernity was cultivated within theocratic soil.

IX. The Fascist Underside of the 1979 Revolution

Beneath the surface of the anti-monarchical and freedom-seeking revolution, in which the middle class also participated, lay a powerful fascistic current, clerical fascism. Leftist intellectuals, myself included, failed to grasp the intimate alliance between urban lumpenism, popular religion, bazaar capitalism, and the Shi‘a clergy.

Right-wing fascistic populism, marked by the mass mobilization of declassed, reactionary strata and fueled by misogynistic sexual repression within a pathological social psyche (read “A State of Femicide”), constituted the revolution’s dark underside.

X. Totalitarianism Is Not Authoritarianism

Totalitarian and authoritarian regimes operate according to distinct logics. Leadership, charisma, ideology, legality, and corruption function differently in each. Journalistic accounts that label Iran’s regime both at once sacrifice analysis for rhetoric and obscure more than they reveal.

XI. The Fallacy of Personalizing Power

Analyses that reduce Iran’s power structure to the “absolute authority” of the Supreme Leader personalize what is in fact a deeply institutional and cartelized system. This analytical shortcut misidentifies power as psychological rather than structural.

XII. From Individuals to Power Blocs

To understand Iran’s Shi‘a theocracy, attention must shift from individuals to power blocs. Hashemi Rafsanjani as a person once wielded more power than Khamenei, but “Hashemi” as a tendency represents a faction of large private capital favoring economic openness and engagement with the West.

This tendency has repeatedly reproduced itself within the power structure as the regime’s aristocracy, not because of personalities but because of its material base. Names change, interests persist.

XIII. War, Militarization, and the True Believers

The eight-year war with Iraq played a decisive role in shaping a leadership class of militarized, intensely “values-based” (ارزشی) true believers in the revolution’s core ideals. This generation emerged hardened, ideologically disciplined, and structurally embedded within the state.

The leadership and rank-and-file of the IRGC and the Basij now constitute some of the most powerful economic and political cartels in the Islamic system, acting simultaneously as guardians of ideology, instruments of repression, and beneficiaries of rent.

XIV. Power Factions and Ideological Mutation

No regime is entirely devoid of reformist tendencies, not even fascist ones. Power factions within the Islamic Republic constantly compete, recruit allies, and jostle for dominance. Some radical Islamists drifted over time toward a Western-inclined political liberalism, while others moved in the opposite direction, toward militarized nationalist social-fascism, and continue to do so.

Ideological mutation cannot be ruled out in principle, but its structural limits must be understood.

XV. Reform, Transformation, and the Mirage of Civil Society

In Iran, the theory of peaceful transformation (استحاله) rested on the assumption that the regime’s dual structure, a “republic” under clerical guardianship, would gradually evolve toward openness, democratic reform, and authentic republicanism. This supposed evolution repeatedly crashed into failure.

Reformist ideology assumed the emergence of a civil society, however incomplete, supported by alliances between reformist elites from above and activists from below. Elections produced hope, semi-state newspapers criticized officials, lawyers bargained in courthouse corridors, and Islamic feminism promised incremental gender equality. The achievements of these efforts over three decades were negligible.

XVI. Neoliberal Turns without Political Liberalization

Like many post-revolutionary state economies emerging from war, Rafsanjani’s era of “Reconstruction” and Khatami’s “Reforms” and Rouhani’s turn to the West pursued privatization, market mechanisms, global trade, and technocratic governance. These shifts demonstrated the regime’s ability to alter its economic paradigm to preserve itself, while retaining its populist ideological shell.

Those who mistook this flexibility for democratic reform committed an error they would eventually pay for.

XVII. The Rise of the System’s Aristocracy

This period saw the emergence of the aghazadeh class, the regime’s aristocracy, alongside widening inequality. At the same time, the Imam’s “true soldiers,” war veterans, sincere Basijis, and ideological militants, felt sidelined and betrayed.

These resentments fueled the resurgence of militarized populism with the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005, under the banner of fighting rent-seekers and elite corruption.

XVIII. Power as Monopoly, Elections as Simulation

Iran’s power system resembles an economy of monopolies. Power is never distributed through a free electoral market. Like oil, carpet, or pistachio monopolies, political power passes to its heirs within the system.

Excluded are citizens as such, professional guilds, labor unions, independent women’s organizations, and bureaucratic employees’ associations.

XIX. Survival, Crisis Management, and the Threshold of Collapse

If rent-seeking remains manageable and ideological legitimacy intact, a fascist regime can survive for decades. But when corruption disrupts rational governance and legitimacy erodes, crises intensify, elite conflicts turn violent, and hungry populations take to the streets.

At that point, the system approaches collapse.

Spring 2013

Copyright: Abdee Kalantari Archives